Dziecięce ReKolekcje Daniela Libeskinda

Clare Farrow w rozmowie z Danielem Libeskindem

Redaktor prowadzący: Jansson J. Antmann

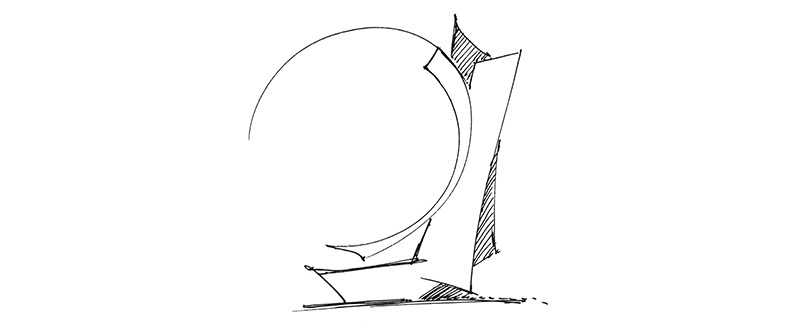

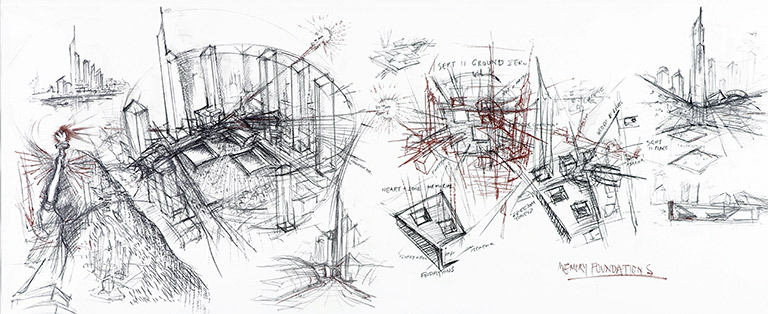

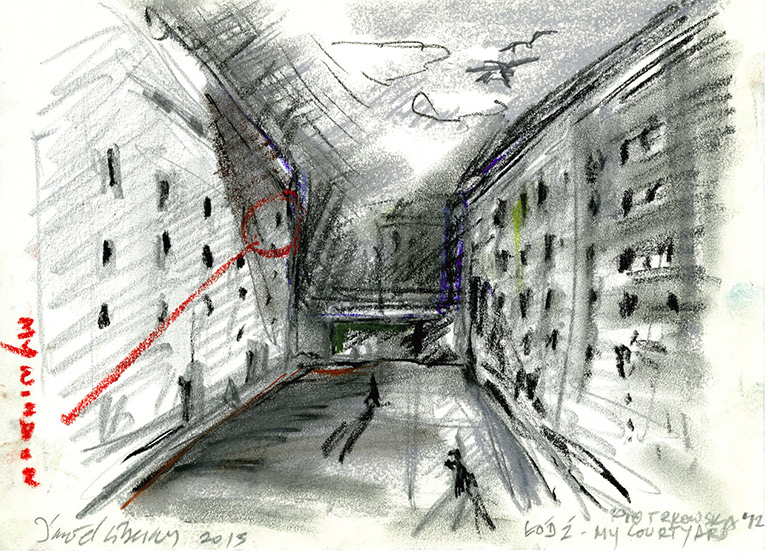

Oto nasz drugi z cykli artykułów ukazujących wspomnienia z dzieciństwa, które ukształtowały niezwykłe artystyczne wizje i realizacje jednego z największych architektów i projektantów dzisiejszych czasów. W tym wydaniu na naszych łamach gości Daniel Libeskind, z którym rozmawiała pisarka i kuratorka Clare Farrow, przygotowując wystawę Childhood ReCollections: Memory in Design, prezentowaną właśnie w Roca London Gallery (wystawa potrwa do 23 stycznia). Jak sama mówi, wspomnienia mogą być świadomie gromadzone, składając się na naszą kreatywną tożsamość, wyzwalane przez obraz, dźwięk albo zapach, powoli pokrywane kolejnymi warstwami przeżyć niczym tkaniny skrywane we wnętrzu pudełka. W wystawie pod kuratelą Clare Farrow przedstawiamy fragmenty tekstów, które zebrane w naszym artykule towarzyszą obrazom, tworzą swoisty nowoczesny gabinet osobliwości albo warsztaty pamięci i designu. W trakcie przygotowywania wystawy u rozmówców Clare Farrow ujawniły się pewne wspólne wzorce: przede wszystkim wpływ, jaki światowe wydarzenia mają na te bardzo osobiste przeżycia, uczucie wyobcowania i odmienności, znaczenie, jakie ma w dzieciństwie obcowanie z muzyką i naturą, relacje między nauką i sztuką, zaangażowanie wszystkich zmysłów w stworzenie unikalnej wizji designu. To może najbardziej prawdziwe w odniesieniu do Daniela Libeskinda, który specjalnie dla tej wystawy stworzył nowe szkice inspirowane chwilami z dzieciństwa. Pokazujemy je w naszym magazynie. Sam architekt zaś tak powiedział o wystawie Farrow: „To fantastyczny projekt, bo pokazuje związek ludzkich wyobrażeń ze światem, przeszłością i przyszłością”.

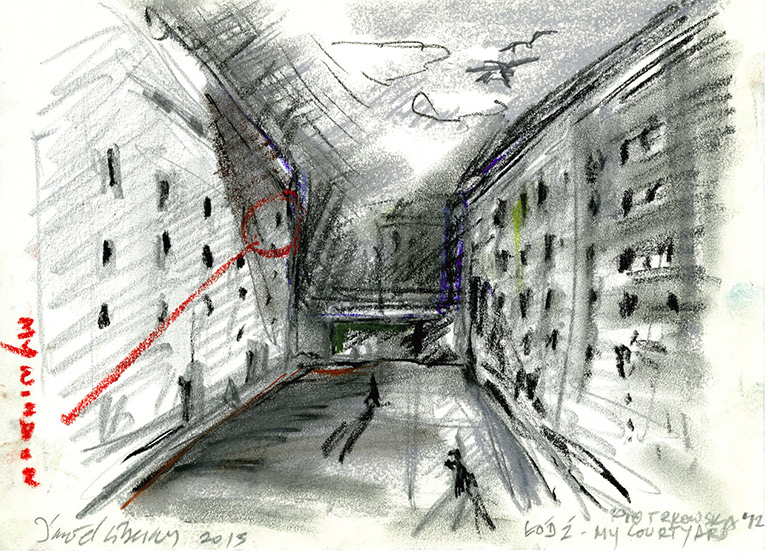

Przed wybuchem II wojny światowej Łódź uważana była za jedno z najbogatszych miast świata. Znana jako „miasto czterech kultur” była wyrazistym przykładem rewolucji przemysłowej. Będąc sercem globalnego rynku tekstylnego, skorzystała z boomu na architekturę w stylu Art Nouveau, z powodzeniem rywalizując nawet z Rygą. Izrael Poznański, swego czasu najbogatszy człowiek na świecie stojący na czele jednej z dynastii handlowych rządzących miastem, zbudował sobie pałac inspirowany Luwrem. Mówiono, że drewniane podłogi ułożono w nim na rublach leżących pionowo, nie na płasko – taki był bogaty. Oczywiście wszystko zmieniło się wraz z nadejściem okupacji nazistowskiej. Zmieniło się oblicze Łodzi i jej pozycja. Miasto stało się synonimem getta Litzmannstadt, a Stacja Radegast centrum transportu ludzkiego towaru z najdalszych zakątków Europy do hitlerowskich obozów śmierci. Rodzicom Daniela Libeskinda udało się przeżyć Holokaust. On sam urodził się w 1946 roku w atmosferze powojennego antysemityzmu.

Daniel Libeskind wspomina: „W powietrzu unosiła się złowroga atmosfera. Łódź cała była szara! Jedna szara ulica za drugą, szarość nie tylko samych ulic, ale życia na nich: ubrani na szaro ludzie zbici w gromadki podążający przed siebie w bezgłośnym marszu. Kochałem wszystko, co miało jakiś kolor, bo otoczenie było takie szare. Bardzo kolorowe były niektóre materiały propagandowe, zwłaszcza te dotyczące Stalina. Dużo czerwieni, zieleni i żółtego, jakby były w technikolorze, błękitne niebo, świecące słońce”.

Patrząc wstecz, Libeskind buduje intrygującą paralelę pomiędzy architekturą a geometrycznym strukturalnym designem kobiecej bielizny wczesnych lat 50. wykonywanej przez jego matkę.

D.L.: „Pasy wyszczuplające z fiszbinami wieloryba wbitymi w gorset dla architektonicznego wsparcia, to było niesamowite! Mama miała maszynę do szycia Singera i wszystko szyła sobie sama. Policja zawsze sprawdzała: skąd brała materiał i czy to, co robiła, nie było nielegalne”.

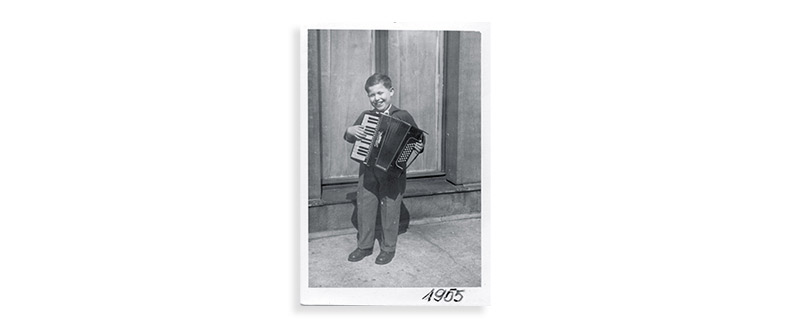

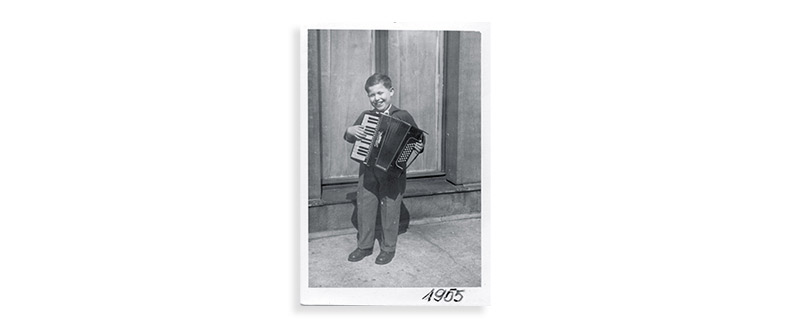

Do przytłaczającego, szarego, powojennego dzieciństwa architekta w Polsce kolor i muzykę wniósł błyszczący, czerwony akordeon.

D.L.: „Chciałem grać na fortepianie. Rodzice też chcieli, żebym grał. Ale bali się wniesienia instrumentu przez podwórko naszej kamienicy, ze względu na okropnych sąsiadów, którzy by powiedzieli: »Widzicie, bogaci Żydzi wnoszą sobie pianino!«. Wręczyli mi więc walizkę, mówiąc: »Oto pianino, w walizce!«.

Miałem czarno-biały akordeon, niemiecki, a potem włoski Sopraci z Neapolu, czerwony i błyszczący iskrami. Był taki piękny. Akordeon naprawdę wniósł radość do świata wokół mnie.”

Libeskind zaczął grać na tym instrumencie w wieku sześciu lat i stał się prawdziwym wirtuozem. Gdy miał 11 lat, jego rodzina przeniosła się do Izraela, gdzie dostał stypendium amerykańsko-izraelskiej America-Israel Cultural Foundation, spotkał Itzhaka Perlmana, zdobywcy tego samego stypendium.

D.L.: „Przeprowadzka do Izraela to była olbrzymia, życiowa zmiana, odkryłem prawdziwy raj, błękitne niebo i rzeczy, o których nie miałem pojęcia, że istnieją. Mój nauczyciel muzyki powiedział, że zapisał mnie na listę kandydatów do stypendium America-Israel Cultural Foundation. Byłem jedyną osobą z walizką!

Widziałem wyraz twarzy trzech jurorów, wśród nich skrzypka Isaaka Sterna, który patrzył na mnie, jak gdybym był z Księżyca. Wyraz ich twarzy zmienił się, gdy zacząłem grać. Kiedy skończyłem, Stern wziął mnie na stronę i powiedział: Wiesz, że wyczerpałeś całą wirtuozerię tego instrumentu? Musisz go zamienić na pianino”.

Coś innego jednak zmieniło się przez tę rozmowę: mój instrument mnie zdradził. Zacząłem interesować się innymi rzeczami: matematyką, malarstwem, rysunkiem.”

W 1959 roku na pokładzie jednego z ostatnich statków z imigrantami Libeskind przybył ze swoimi rodzicami i siostrą do Nowego Jorku. Zamieszkali w Bronksie.

D.L: „Stałem na pokładzie i patrzyłem na fantastyczne miasto wznoszące się z wody, ta linia horyzontu, Statua Wolności, było w tym tyle euforii, tak bardzo daleko od świata, który znałem!”.

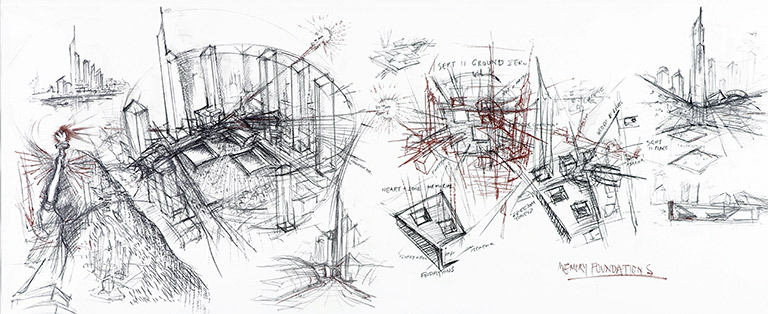

Libeskind studiował architekturę w Cooper Union (dyplom uzyskał w 1970 roku), a historię i teorię architektury na Uniwersytecie Essex (dyplom w 1972). W 1989 roku wygrał międzynarodowy konkurs na projekt Muzeum Żydowskiego w Berlinie, które miało zostać otwarte 11 września 2001 roku − zaledwie kilka godzin później, kiedy tego dnia doszło do ataku na WTC w Nowym Jorku. Otwarcie muzeum odwołano. W 2003 roku został głównym architektem nowego World Trade Center w Nowym Jorku z wygranym projektem Memory Foundations – Fundamenty pamięci.

D.L.: „Dla mnie Nowy Jork jest odzwierciedleniem wszystkiego tego, co dla większości ludzi wydaje się czymś oczywistym: wolnością jednostki, niezależnością, pochwałą indywidualności. Dla mnie to po prostu prawda, żadna metafora”.

Twórczość Libeskinda to między innymi seria zleceń na budowę muzeów, głęboko osadzonych w filozofii, literaturze i poezji. W tych projektach silnie obecne są emocje, z wieloma odniesieniami do muzyki.

D.L.: „W muzyce nie można oddzielić naukowego aspektu dźwięku od zawartych w nim emocji. Bez nich byłoby to tylko mechaniczne odtwarzanie muzyki. Nie byłby to żaden występ. A przecież muzyka to nie jest żadna techniczna operacja. Często myślę o tym, kiedy patrzę na przestrzeń, zanim ją zobaczę, najpierw się w nią wsłuchuję. Dźwięk miejsca zamiast obrazu”. |

Wybrane projekty Daniela Libeskinda:

– Muzeum Feliksa Nussbauma (1998);

– Muzeum Żydowskie w Berlinie (2001);

– Imperial War Museum North w Manchesterze (2002);

– Atelier Weil, prywatna galeria w Mallorce w Hiszpanii (2003);

– The Graduate Student Centre w londyńskim Metropolitan University (2004);

– Duńskie Muzeum Żydowskie w Kopenchadze (2004);

– Tangent − biurowiec dla korporacji Hyundai w Seulu (2005);

– Memoria e Luce, pomnik upamiętniający ofiary 11 września w Padwie (2005);

– Wohl Centre, Bar Ilan University w Tel Awiwie (2005);

– Pawilon Royal Ontario Museum w Kanadzie (2007);

– Glass Courtyard, nowy pawilon Muzeum Żydowskiego w Berlinie (2007);

– The Ascent at Roebling’s Bridge, ekskluzywna rezydencja w Kentucky (2008);

– Contemporary Jewish Museum w San Francisco, California (2008);

– Apartamentowiec Złota 44 w Warszawie (2013);

– Arsenał w Muzeum Wojskowo-Historycznym Bundeswehry w Dreźnie (2013).

Wszystkie cytaty, wypowiedzi Daniela Libeskinda pochodzą z wywiadu Clare Farrow przeprowadzonego na potrzeby realizacji wystawy Childhood ReCollections: Memory in Design, March 2015 © Daniel Libeskind and Clare Farrow, 2015.

Childhood ReCollections of Daniel Libeskind

Clare Farrow in conversation with Daniel Libeskind

Editor: Jansson J. Antmann

We continue our special series of articles revealing the childhood recollections that have shaped the outstanding visions and work of some of the greatest architects and designers of our time. This issue we welcome Daniel Libeskind, who was interviewed by writer and curator Clare Farrow in preparation for her exhibition, Childhood ReCollections: Memory in Design, currently showing at the Roca London Gallery (until 23rd January). As she says, memories can be consciously retained as part of a creative identity, or triggered by an image, sound or scent, or slowly uncovered in a sequence of layers, like materials stored inside a box. In the exhibition curated by Farrow, the resulting text fragments, some of which are presented here, combine together with connections and materials to form modern-day cabinets of curiosities, or working studios of memory and design. In the process of making the exhibition, certain patterns emerged too: the impact of world history on these very personal stories; themes of displacement and difference; the importance of nature and music in childhood; the links between science and art; and the involvement of all the senses in establishing a unique design vision. This could not be truer than in the case of Daniel Libeskind, who created new sketches, inspired by his childhood memories, especially for the exhibition, and shown here on the pages of our magazine. Libeskind said of Farrow’s exhibition, “It is really a fantastic project, because it is such an interesting connection of people’s ideas of the world, to the past and to the future.”

Before the outbreak of World War II, Łódź was reputedly the wealthiest city in the world. The ‘City of Four Cultures’, as it was known, was a shining example of the Industrial Revolution. The heart of the global textiles trade, it benefited from a boom in Art Nouveau architecture to rival even Riga. Izrael Poznanski, at the time one of the richest men in the world and head of one of the industrial dynasties that dominated the city, built himself a palace inspired by the Louvre. It was said that he’d insisted the wooden floors be laid on a bed of rubles stacked on their side, not flat – he was that wealthy. Of course, that all changed with the Nazi occupation, as did the city’s reputation. Łódź became synonymous with the Litzmannstadt ghetto, while its Radegast railway station became the epicentre of a distribution network designed to carry its human cargo from the farthest reaches of Europe to the Nazi death camps. Daniel Libeskind’s parents were survivors of the Holocaust and he was born in 1946 into an atmosphere of post-war anti-Semitism.

“There was a very pernicious atmosphere hanging in the air. Łódź was totally grey! One grey street after another; the greyness not just of the streets but of life in those streets; the people in grey, huddling and conforming to a kind of silent walk. I loved anything that had colour in it, because it was such a grey environment. Some of the propaganda material, on Stalin in particular, was in brilliant colours… There was a lot of red, but green too, and yellow; they seemed to have a kind of Technicolor idea; blue skies, sunshine.”

Looking back, Libeskind draws an intriguing parallel between architecture and his mother’s geometric, structured designs for women’s underwear in the early 1950s.

“Corset girdles, with whalebones stuck in them for architectural support, they were amazing! She had a Singer sewing machine, so she did everything herself. The police were always checking: where did she get the materials, what was she doing that was illegal?”

In the end, it was a sparkling red accordion that brought colour and music into the oppressive, grey, post-war childhood world of Poland for Daniel Libeskind.

“I wanted to play the piano […] My parents wanted to, but they were too afraid to bring the piano through the tenement courtyard, because of our terrible neighbours who would say, ‘You see, here are the rich Jews getting the piano!’ So they brought me a suitcase, and said to me, ‘Here is the piano, in a suitcase!’.

I had a black and white one, which was a German one, and then later on I had a Soprani, the Italian accordion from Naples, which was a brilliant red, sparkling with sparkles. It was so beautiful. The accordion really brought joy to the world around me.”

He began playing the accordion at the age of 6, and became a child virtuoso. At the age of 11, his family moved to Israel, where he won an America-Israel Cultural Foundation scholarship, meeting the young violinist Itzhak Perlman, who was one of the other scholarship winners.

“It was a life change when I moved to Israel, and discovered a true paradise, with blue skies and things I never knew existed. My music teacher told me that he had inscribed my name for the America-Israel Cultural Foundation competition… I was the only person there with a suitcase! I saw the expressions of the three judges, including the violinist Isaac Stern, looking at me as if I was from the moon. But their e xpressions changed when I began to play. When I had finished, Stern took me to one side and said, ‘Do y ou know you have already exhausted the virtuosity of this instrument? You have to change to the piano.’

…Something had fundamentally changed in that short conversation with Isaac Stern: the betrayal of my instrument. I began to get interested in other things: mathematics, painting, drawing.”

In 1959 he arrived in New York with his parents and sister on one of the last immigrant boats to the US, settling in the Bronx. “

…standing on those decks, […] to see the amazing city open up from the water, that skyline, the Statue of Liberty, […] it was something so elating, so outside of this world that I ever knew!”

He studied architecture at Cooper Union (completing his degree in 1970), and theory at the University of Essex (PhD, 1972). In 1989 he won the international competition to design the Jewish Museum in Berlin, which was scheduled to open on September 11, 2001 (just hours later on that day in Berlin, the planes hit the World Trade Centre towers in New York, and the museum cancelled its opening). In 2003 he was selected as the master plan architect for the World Trade Center site in New York, the winning concept entitled ‘Memory Foundations’.

“To me New York is the affirmation of all those things that most people just take for granted: liberty, freedom, and individuality. To me it was true; it wasn’t a metaphor.”

Libeskind’s work, which includes a series of museum commissions, is deeply informed by philosophy, literature and poetry. It is also characterized by a complex emotive precision that has strong parallels with music.

“In music, you cannot separate the scientific piece of music from its emotion. Without the emotion it would just be a mechanical performance. It would not really be a performance at all. Without emotion, there would be no music. “[In design] even an abstract line, just drawing one line, is an emotion. It’s not just a technical operation. I often think that when I look at a space I actually hear it before I see it. It’s the sound of places, before I look at them.” |

The extracts / quotes are all from an interview by Clare Farrow for Childhood ReCollections: Memory in Design, March 2015, © Daniel Libeskind and Clare Farrow, 2015