Dziecięce ReKolekcje Kengo Kumy

Clare Farrow w rozmowie z Kengo Kumą

Redaktor prowadzący: Jansson J. Antmann

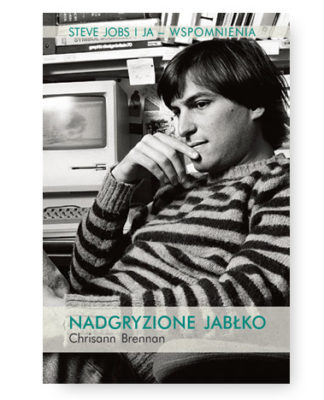

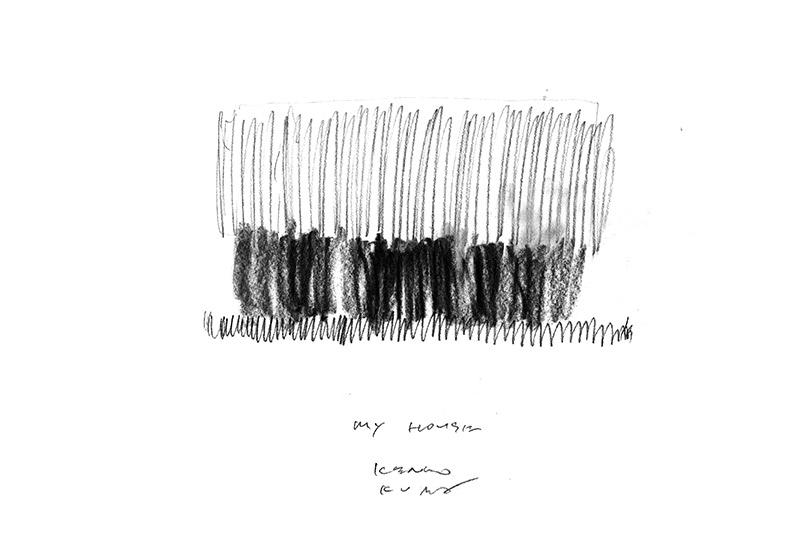

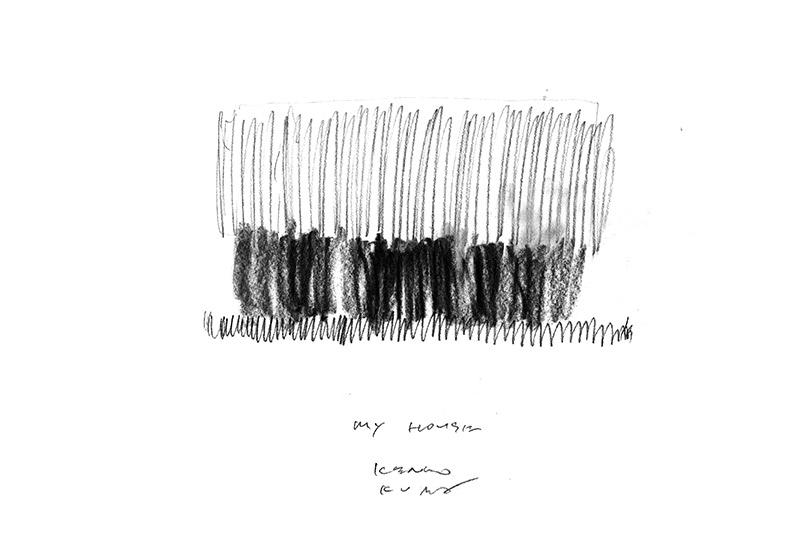

Bohaterem trzeciego materiału naszej specjalnej serii zapoczątkowanej wywiadem z Zahą Hadid przedstawiającej inspiracje największych architektów i projektantów naszych czasów jest Kengo Kuma. Rozmowę ze słynnym japońskim architektem przeprowadziła Clare Farrow, pisarka i kuratorka wystawy Childhood ReCollections: Memory in Design, która została otwarta w Roca London Gallery jesienią zeszłego roku. Na wrzesień zaplanowane jest ponowne otwarcie, tym razem w Roca Barcelona Gallery. Jak podkreśla Clare Farrow zarówno Daniel Libeskind (bohater naszego poprzedniego wydania), jak i Kengo Kuma byli bardzo zadowoleni z udziału w projekcie. − Jestem zaszczycona faktem, że ci projektanci odpowiedzieli z takim zainteresowaniem i entuzjazmem na zaproszenie do udziału w wystawie − mówi Farrow. − Jestem zachwycona, że Kengo Kuma i Daniel Libeskind wykonali, specjalnie na tę wystawę, nowe rysunki inspirowane przeżyciami z dzieciństwa. Te unikalne rysunki pokazujemy na stronach naszego magazynu, poczynając od najwcześniejszych wspomnień, ścian z ziemi i papieru washi w jego domu z dzieciństwa. Architekt odkrywa przed nami inspiracje, które stoją za jego twórczością, a zwłaszcza za nagrodzonym domem Great (Bamboo) Wall w Pekinie (2002), siedzibą japońskiego oddziału koncernu LVMH w Osace (2003) czy wreszcie za projektem nowej świątyni designu w Dundee, V&A, która ma być otwarta w 2018 roku.

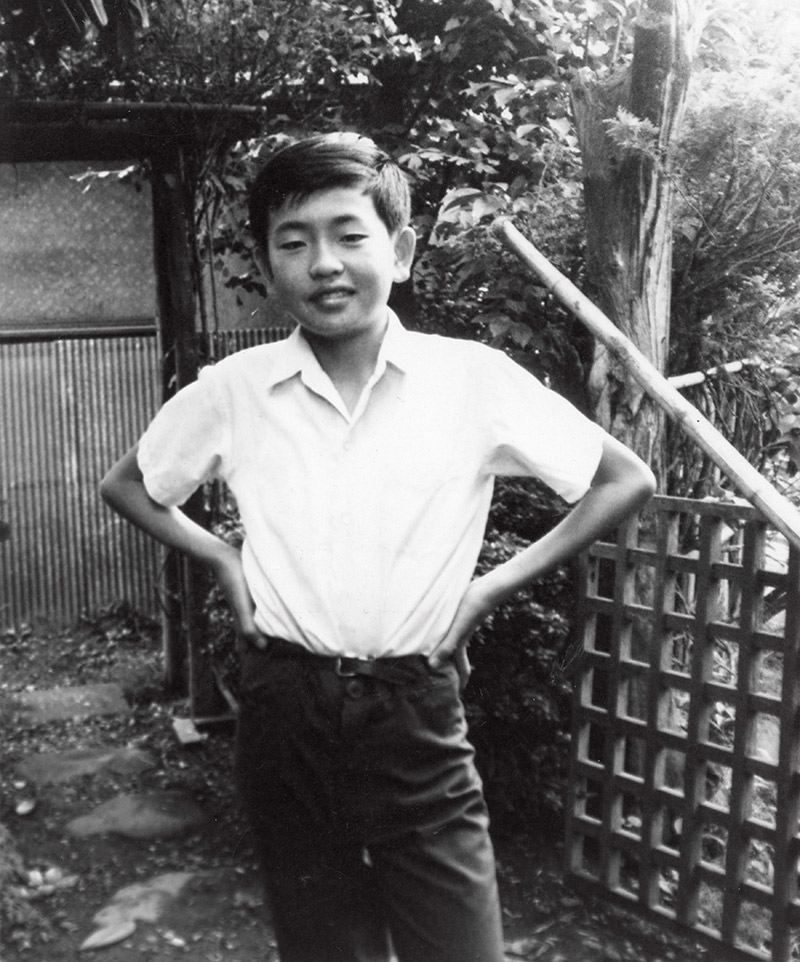

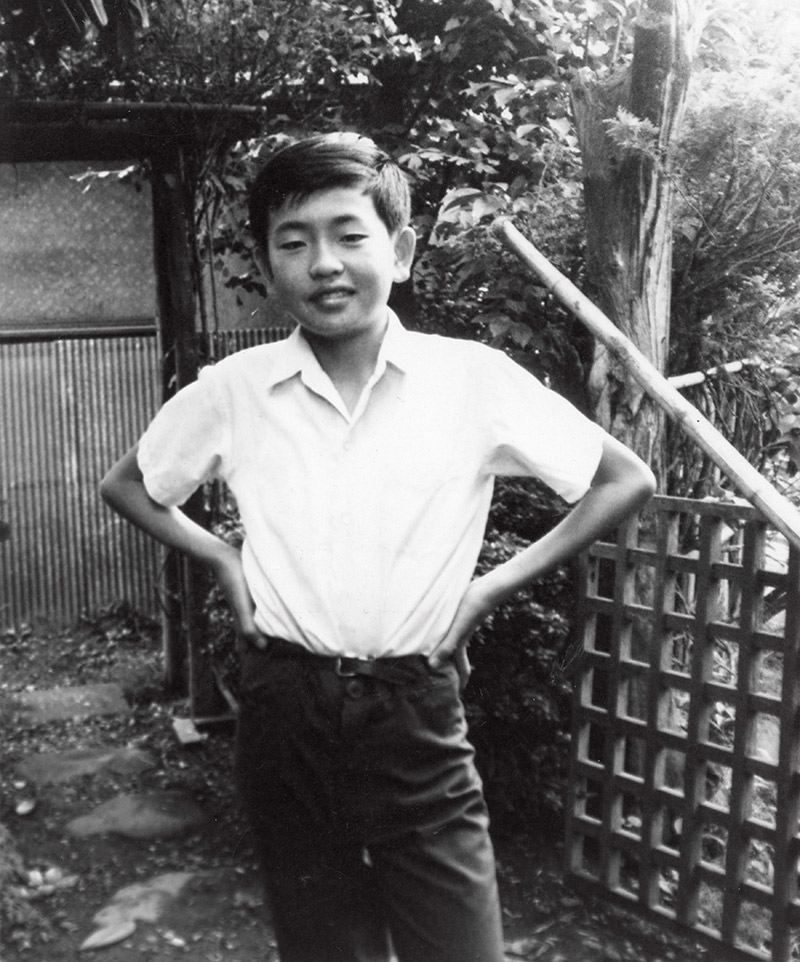

Kengo Kuma urodził się w 1954 roku w Jokohamie, stolicy prefektury Kanagawa. Było to szczególnie dogodne miejsce dorastania dla młodego architekta, zwłaszcza że miasto dwukrotnie odbudowywano. Jokohama to największy port morski w Zatoce Tokijskiej i, jako taki, narażony na działanie żywiołów, co ukazuje słynny drzeworyt z 1833 roku japońskiego artysty Katsushiki Hokusai „Wielka fala w Kanagawie”. Jednak prawdziwym zagrożeniem okazało się wielkie trzęsienie ziemi Kantō w 1923 r., którego następstwem było tsunami siejące spustoszenie w regionie. Następnie, w 1945 roku, miasto zostało zbombardowane przez Amerykanów i po raz kolejny niemal doszczętnie zniszczone. W tej atmosferze odbudowy po katastrofach, jednej naturalnej, a drugiej spowodowanej przez człowieka, urodził się Kuma. Jest być może coś ironicznego w stwierdzeniu, że wychowywał się on w jednym z nielicznych zachowanych domów, mogąc obserwować tradycyjne budownictwo i rosnący wokół niego nowy świat z betonu.

Kengo Kuma wspomina: „Dom, w którym się wychowywałem, był drewnianym, jednopiętrowym budynkiem, sprzed drugiej wojny światowej. Mocno się różnił od powojennego stylu, zwłaszcza pod względem zastosowanych materiałów, jak również rozkładu pomieszczeń. Dzisiaj używam tych naturalnych materiałów w mojej pracy, z jednej strony kierując się nostalgią, ale i podziwem z drugiej”. Na design miały też wpływ pokoje wyłożone tatami, które zaczęły zanikać w powojennych, urządzanych na zachodnią modłę domach. − Wyjątkowa elastyczność tatami znajduje odbicie w moich projektach − mówi Kengo Kuma. (Tatami to mata z ryżowej słomy używana do wykładania podłóg. Ma standardowy wymiar, jej długość jest zawsze dwa razy większa niż szerokość. Dokładne zasady określają, ile i w jaki sposób powinno być tatami w pokoju).

Ta tradycja, jak i „starzejące” się domy z lat 30. z jego dzieciństwa widoczna jest w eksperymentach ze światłem, przezroczystością i materialnością Kengo Kumy.

K.K.: „Innym silnym obrazem był shoji (ekran z drewnianych ramek wypełnionych tradycyjnym papierem washi) i przebijające przez niego światło. Widziałem, jak zamykając shoji, pokój zamieniał się w zupełnie inny świat. Często mówię, że nie lubię betonu, ale tak naprawdę najbardziej nie cierpię światła z fluorescencyjnych i aluminiowych ram okiennych. Nie mogę znieść ich zimnej materii. Kiedy odwiedzałem moich przyjaciół w ich mieszkaniach z betonu, uderzał mnie nie tyle fizyczny wygląd mieszkań, ile zupełnie inne »czucie« miejsca niż w moim starym, drewnianym domu?”.

To przede wszystkim reakcja na światło przyciągnęła Kumę do architektury.

K.K.: „Poraził mnie efekt świetlny, który uzyskał Kenzo Tange w projekcie obiektów olimpijskich w Tokio (1964 r.). To robiło więlkie wrażenie, większe niż betonowa forma. (…) Wtedy po raz pierwszy uświadomiłem sobie istnienie i rolę architekta”.

Kuma rozpuszcza lub „rozbija” materiał, czasami składając go jak origami, używając innowacyjnych technik, by połączyć swoje formy z naturą, poezją, muzyką, sztuką i nauką. Często pisze o „ekranie” pomiędzy światem zewnętrznym i wewnętrznym, „pustce” przeznaczonej na wiejący przez nią wiatr i co najważniejsze, o „mocy miejsca”.

K.K.: „Tak, jestem produktem miejsca − domu i jego naturalnego środowiska − satoyama (…). To naturalna przestrzeń zwykle usytuowana poza albo wokół miasta. Satoyama na naszym podwórku to były głównie bambusowe pałki. Chodziłem po ziemi, w której rosły bambusy, i wdychałem zapach ich liści. To było dla mnie naturalne środowisko.

Moja słabość dla dziur i przejść wynika z moich dziecięcych doświadczeń, właśnie z obecności satoyama z tyłu domu. Były tam też we wzgórzu pozostałości kryjówek przed bombami. To było wspaniałe miejsce do zabawy. Uwielbiałem się tam chować, byłem wtedy całkowicie odcięty od życia na zewnątrz. Może właśnie to doświadczenie skłoniło mnie do budowania dziur i sekretnych przejść w moich projektach”.

Dla Kumy, tak jak dla Daniela Libeskinda, niezwykle ważna była muzyka. Podobnie jak rysunek, który odegrał tak ważną rolę w dorastaniu Zahy Hadid. Z kolei pisanie nigdy nie pasjonowało młodego Kumy, który zaczął je lubić dopiero później.

K.K.: „Uczyłem się gry na pianinie, więc znajomo brzmią dla mnie niektóre kawałki Bacha. Pamiętam fugę małą g-moll. Jako dziecko lubiłem rysować, ale nie pisać. Przyjemność pisania przyszła później. Zostałem architektem i poznałem radość przedstawiania ludziom architektury za pomocą słów”.

Dzisiaj Kuma jest profesorem w Graduate School of Architecture na Uniwersytecie w Tokio, gdzie studiował, zanim dostał się na Uniwersytet Columbia w Nowym Jorku. Dostał tytuł doktora na Keio University w 2001 roku. W 2014 wydał książkę Boku no Basho (Moje miejsce), w której pisze:

„Jestem świadomy tego, jak mój sposób patrzenia, kształt, jaki przybierają moje działania i formułowanie myśli, wszystko istnieje i zależy od głębi miejsc, w których byłem. Czuję, że zrozumiałem, że jestem jak drzewo, które rośnie w lesie”. |

Wybrane projekty Kengo Kumy:

– Water/Glass (1995);

– Stage in Forest, Centrum Toyoma (1997 − Instytut architektury, Japońska Nagroda Roku);

– Muzeum Kamienia (2000, Międzynarodowa Nagroda − Architektura Kamienia 2001);

– Muzeum Bato-machi, Hiroshige (2001 − Tytuł Murano 2001);

– Tee Haus, Frankfurt (2007);

– Suntory Museum of Art, Tokio (2007);

– Wieżowiec Drzewo, Tokio (2015).

Wszystkie fragmenty wypowiedzi i cytaty pochodzą z wywiadu Clare Farrow przeprowadzonego na potrzeby wystawy Childhood ReCollections: Memory in Design, marzec 2015 © Kengo Kuma i Clare Farrow, 2015. Nie dotyczy fragmentu z książki Boku no Bosho, wyd: Daiwa Shobo, 2014 © Kengo Kuma.

Childhood ReCollections of Kengo Kuma

Clare Farrow in conversation with Kengo Kuma

Editor: Jansson J. Antmann

Kengo Kuma is the subject of the third article in our special series, which began with Zaha Hadid and explores what shaped the outstanding visions and work of some of the greatest architects and designers of our time. Writer and curator Clare Farrow interviewed Kuma in preparation for her exhibition, Childhood ReCollections: Memory in Design, which opened at the Roca London Gallery last autumn. The exhibition is scheduled to reopen at the Roca Barcelona Gallery in September. As Farrow recalled, both Daniel Libeskind, who was featured in our previous issue, and Kengo Kuma were keen to be involved. “I feel very honoured that these designers have responded with such interest and enthusiasm to the project,” Farrow said. “I am also delighted that Kengo Kuma and Daniel Libeskind have created new sketches, inspired by their childhood memories, specially for the show.” These sketches are featured on the pages of our magazine. From his earliest memories of the earthen wall and washi papers in his childhood home, Kengo Kuma uncovers the inspiration behind his own work, which includes the award-winning Great (Bamboo) Wall house in Beijing (2002), the LVMH Group Japan Headquarters in Osaka (2003) and the new Dundee branch of that ‘temple’ to design, the V&A, due to open in 2018.

Kengo Kuma was born in 1954 in Yokohama, the capital of the Kanagawa Prefecture. It was an apt location for the young architect to grow up in; given it had to be rebuilt twice. Yokohama is the largest deep-water port in the Tokyo Bay and, as such, had always been threatened by the elements, as depicted in Katsushika Hokusai’s iconic 1833 woodblock print, the ‘Great Wave off Kanagawa’. However it was the Great Kantō earthquake in 1923, which finally caused the tsunami that devastated the region. Then followed the US bombings in 1945, which again severely damaged the city. Into this environment of rebuilding after both natural and man-made catastrophes, Kuma was born. It is perhaps ironic that Kuma was in fact brought up in one of the few houses to survive, exposing him to the traditional ways of building, as a new world of concrete rose up around him.

“The house where I was brought up was a wooden one-storey house, built before the Second World War. It hugely differed from any post-war style, especially in the materials and the planning … I now use those natural materials in my work, partly with a sense of nostalgia, and some admiration.

Also the tatami rooms, which began to cease in the post-war westernized houses, influenced by design a lot. The unique flexibility of tatami is often reflected in my designing.” [Ed.: Tatami is a rice straw mat used for flooring. It comes in a standard size, with an aspect ratio of 2:1 – i.e. the length is exactly twice the width. Strict rules govern the number and layout of tatami mats in a room.]

Kuma’s experiments with lightness, transparency and materiality can be traced to such traditions too, and the ‘ageing’ 1930’s house of his childhood.

“Another strong image for me was the shoji [the paper screen in a wooden latticed frame] in relation to the light coming through it. I learned that just by closing, the shoji could take the room to a completely different world.

I often say that I do not like concrete, but what I hated most was the light from fluorescent and aluminium sash. I couldn’t bear their cold materiality. I used to visit friends’ apartments in concrete, and what struck me about them was not the physical appearance of the apartment, but a very different ‘feel’ of the place from my old wooden house.”

It was Kuma’s reaction to light that attracted him to architecture in the first place.

“I was knocked out by the effect of light that Kenzo Tange designed for those Olympic facilities [in Tokyo, 1964], This was a bigger impact than the form of concrete […] this was the first time I became aware of the existence and role of the architect.

Kuma dissolves or ‘atomises’ material, sometimes folding it like origami, using innovative techniques to connect his forms to nature, poetry, music, art and science. He writes prolifically about a ‘screen’ between outside and inside, a ‘void’ for the wind to pass through, and most importantly, the ‘power of place’.

“YES, I am a product of the place – of the house and its natural environment – the satoyama […] It’s a semi-natural area usually located behind or around a town. The satoyama in our backyard was mostly bamboo thicket. I used to tread on the ground where the bamboo were growing, and feel the aroma of their leaves. It was a natural environment for me.

My fondness for holes or passageways comes from my childhood experience, again from that satoyama behind the house. Back then there were still some bomb shelters remaining in the hill and that was our ideal playing field. I loved the time of hiding in the shelter, totally detached from the life outside. Perhaps that experience directed me to use the holes or secret passages in my work.

Music was important to Kuma, as it had been to Daniel Libeskind. So too drawing, which had played such a vital role in Zaha Hadid’s upbringing. Ironically, writing was not a passion of the young Kuma, who only later came to enjoy it.

“I used to be given piano lessons, so some of the pieces by Bach sound very familiar to me. What I remember is Bach’s Little Fugue in G minor. I loved drawing as a child, but definitely not writing. The pleasure of it came after I became an architect and knew the delight of telling people about architecture in words.”

Today, Kuma is Professor at the Graduate School of Architecture at the University of Tokyo, where he himself studied before attending Columbia University in New York. He was awarded a PhD from Keio University in 2001. In 2014 he published ‘Boku no Basho’ (My Place), in which he wrote:

‘I am keenly aware of the fact that my way of looking at things, the form that my actions take and the formulation of my thoughts, all exist in and depend upon the depths of the places that I have been. I sense that I came to realize that I am like the tree that grows in the forest.’ |

The extracts and quotes are all from an interview by Clare Farrow for Childhood ReCollections: Memory in Design, March 2015, © Kengo Kuma and Clare Farrow, 2015, except for the extract from ‘Boku no Bosho’, publisher: Daiwa Shobo, 2014, © Kengo Kuma.