Dziecięce ReKolekcje Philipa Treacy

Clare Farrow w rozmowie z Philipem Treacy

Redaktor prowadzący: Jansson J. Antmann

W drugiej odsłonie serii Childhood ReCollections w naszym aktualnym numerze żegnamy na chwilę świat architektury, by podejrzeć wczesne inspiracje legendarnego projektanta kapeluszy Philipa Treacy. Jak Zaha Hadid, Daniel Libeskind i Kengo Kuma, z którymi spotkaliśmy się już na naszych łamach, pisarka i kuratorka Clare Farrow rozmawiała z Treacy, przygotowując swoją wystawę Childhood ReCollections: Memory in Design, otwartą w zeszłym roku w Roca London Gallery. Przedstawiała ona sześć osobistości świata architektury i designu, wśród nich pięciu architektów. Zainspirowana słowami Chanel „Moda jest architekturą: to kwestia proporcji”, Farrow rozciągnęła temat wystawy poza obszar architektury i designu wnętrz na świat mody. Pierwsze odniesienia do architektury znaleźliśmy u Daniela Libeskinda, który wspominał geometryczne, strukturalne projekty kobiecej bielizny autorstwa swojej matki. Teraz wchodzimy w świat mody, głębiej pokazując inspiracje projektanta kapeluszy Philipa Treacy, którego dziecięce wspomnienia również pełne są światła, koloru, natury, zapachów, tkanin, struktur, a nade wszystko, wyostrzonej wrażliwości na świat.

Syn piekarza i szósty z ósemki rodzeństwa Philip Treacy urodził się w 1967 roku w Ahascragh, w hrabstwie Galway. Istnieje wprawdzie wzmianka o tej niewielkiej irlandzkiej miejscowości w historycznych rocznikach, ale tak skromne początki wydają się stać w sprzeczności z zawrotną karierą, która stała się jego udziałem. Wśród szacownej klienteli Philipa Treacy znaleźli się członkowie rodziny królewskiej i królewskiego baletu, Lady Gaga czy aktorzy występujący w Harry Potterze. Na pierwsze eksperymenty z projektowaniem pozwoliło mu pierze matczynych kur, kaczek i bażantów oraz szycie na maszynie, do której miał się nie dotykać, ubranek dla lalek siostry. Wyjechał do Dublina na studia w National College od Art and Design, następnie w 1988 dostał stypendium w londyńskim Royal College of Art. Był jeszcze studentem, kiedy w 1989 roku, podczas sesji zdjęciowej dla magazynu Tatler poznał redaktorkę modową Isabellę Blow, która odkryła Alexandra McQueena i zainwestowała w jego pierwszą kolekcję. Niedługo potem Treacy projektował kapelusze Karla Lagerfelda w domu mody Chanel. Po ukończeniu szkoły w 1990 roku otworzył swoje studio w Londynie i rozpoczął współpracę z wieloma domami mody, w tym Givenchy, Valentino i Alexander McQueen. W 2007 roku został odznaczony honorowym Orderem Imperium Brytyjskiego. Niezwykłe osiągnięcie dla chłopaka z małej wioski liczącej około 500 mieszkańców, gdzie wszyscy się znali.

Philip Treacy wspomina: „Mój świat wydawał mi się tak fascynujący, ale mój odbiór zewnętrznego świata był kolorowany przez moją siostrę i braci. Kiedy podrośli przeprowadzili się do Londynu i Londyn stał się dla mnie zamkiem Camelot”.

W latach 70. mały Treacy mieszkał przy drodze wiodącej do kościoła, co miało olbrzymi wpływ na jego zmysł estetyczny. Uwielbiał patrzeć na nadjeżdżające panny młode w ich egzotycznych sukniach ślubnych. Był na każdej ceremonii zaślubin, niezaproszony.

P. T.: „Kiedy ukazywała się panna młoda, nie mogłem w to uwierzyć. To było całe moje odczuwanie mody. (…) Nie byłem wtedy zbytnio nastawiony na kapelusze, to był raczej czas fantazji. A kiedy wszyscy goście opuszczali kościół, zbierałem porozrzucane konfetti.

Jako dziecko pojmowałem piękno w sposób wyjątkowy, jak fantastyczny film albo kościół. Wszystkie kolory, jakich używam, są w rzeczywistości kolorami Kościoła katolickiego: głęboki róż szat księży albo blady błękit, paleta moich kolorów jest religijna, to piękne złoto damasceńskie. Wciąż projektuję dla Madonny (z kościoła)”.

Pokonywanie granic i walka ze stereotypami zawsze przychodziło Treacy’emu w sposób naturalny, znajdował wsparcie we wszystkich właściwych miejscach, nawet w szkole.

P. T.: „Zauważyłem, że dziewczynki mają zajęcia z szycia, a chłopcy nie. Kiedy ma się sześć lat nie ma się właściwie żadnych zahamowań, więc zapytałem nauczycielkę, czy nie mógłbym też w nich uczestniczyć. Odpowiedziała: OK i nauczyła mnie szyć. Potem uczyła szycia wszystkich chłopców.

Pamiętam dokładnie dzień, kiedy jeden z sąsiadów zapytał mojego ojca: czy nie wydaje ci się dziwne, że twój syn szyje sukienki dla lalek? Podsłuchałem, co odpowiedział na to mój ojciec: cokolwiek go uszczęśliwia. To było niesamowite.

Dorastając w dużej rodzinie, widzi się, że każdy jest inny, każdy się dostosowywał. To dobra lekcja życia. Ale też w irlandzkich małych miasteczkach akceptuje się ludzką indywidualność. (…) Myślisz, że to specyfika miejsca, ale to miejsce jest wciąż tutaj. Tym bardziej to wyjątkowe w odniesieniu do ludzi”.

Jego najwcześniejsze wspomnienia prostego beretu, który nosiła jego matka, stworzyły podstawę do projektowania kapeluszy.

P. T.: „Zawsze wyraźnie pamiętam (…), jak zastanawiałem się, dlaczego tak ważne było dla niej ułożenie nakrycia głowy, spędzała sporo czasu, dopasowując go, nie było tak sobie po prostu włożone. Układała nakrycie głowy, pracując twarzą i układając włosy. To było bardzo proste nakrycie głowy, ale ważne”.

Treacy uwielbia tworzyć piękne przedmioty i eksperymentować z nowymi kształtami. To podstawa tego, kim jest.

P. T.: „Fizyczność procesu tworzenia z dwuwymiarowego materiału na trójwymiarowy zawsze była we mnie, bo zawsze lubiłem robić coś z niczego. W dalszym ciągu to lubię. W robieniu chleba czy ciasta albo ubrań, kapeluszy lub biżuterii jest coś zadziwiającego: satysfakcja z robienia pięknych rzeczy albo czegoś najlepszego wykorzystując swoje umiejętności, to właśnie świadczy o naszym człowieczeństwie”.

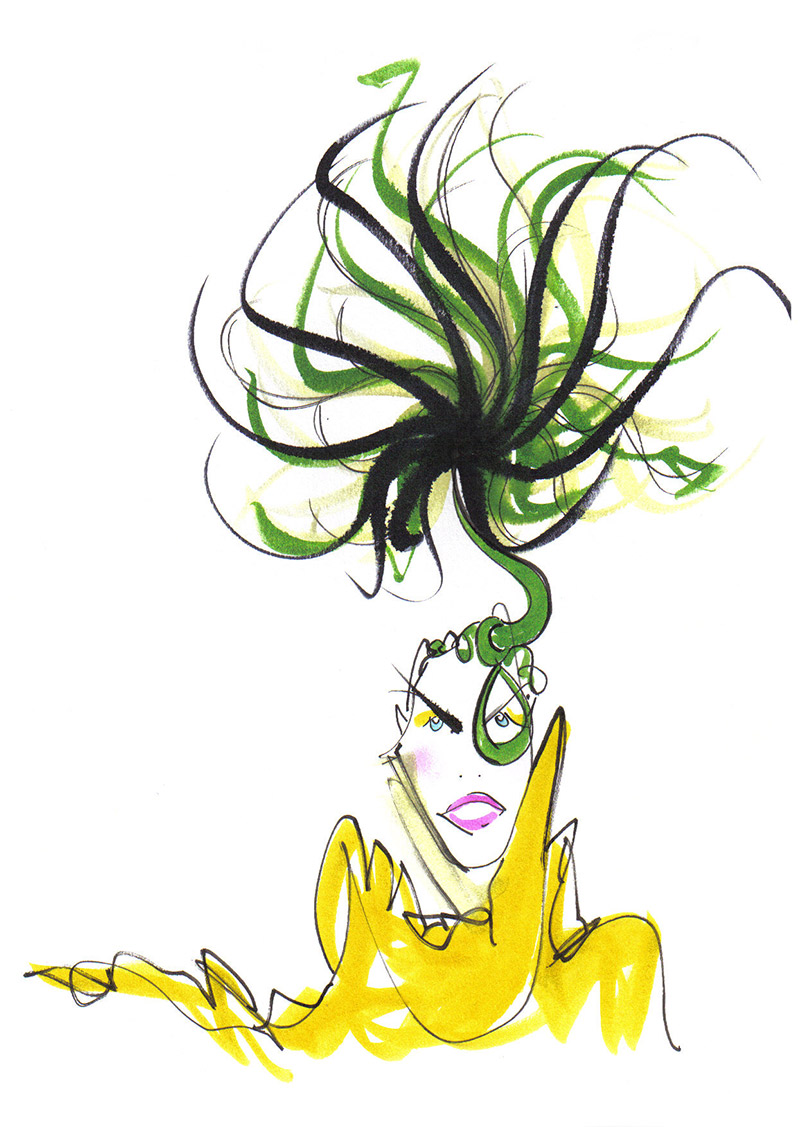

W poszukiwaniu tego natura i materiały, którego otaczały, jak kwiaty czy ptaki w ogrodzie, są nadal źródłem jego inspiracji.

P. T.: „Naśladowałem naturę za pomocą tkanin. Wymyśliłem, że liście zrobię, przypalając świeczką rąbek taniego poliestru, który marszczy się i zwęgla, przypominając brzeg liścia. Zawsze fascynowały mnie pióra, uważałem, że to absolutnie niezwykły materiał. Pióro jest jak membrana, nic nie waży, jest przezroczyste, to jak żywy, oddychający materiał, nie przypomina żadnego innego, ma w sobie magię. Jeden z pierwszych kapeluszy zrobiłem właśnie z piór kurczaka mojej mamy, i trafił na Ascot!”.

Podobnie jak architekt Kengo Kuma, Treacy również widzi w naturalnych materiałach antidotum dla dzisiejszego świata betonu.

P. T.: „Kiedy stajemy się bardziej miastowi, potrzebujemy więcej ogrodów i kwiatów, które by nam przypominały, że nie tylko beton jest na świecie. Kiedy pracuje się przez 23 lata w branży modowej, dochodzi się do wniosku, że luksus to wcale nie jest torebka Louis Vuitton. Natura jest luksusem. Ptasi śpiew jest luksusem. Wyobraźnia jest luksusem. |

Wszystkie fragmenty/cytaty pochodzą z wywiadu Clare Farrow na potrzeby wystawy Childhood ReCollections: Memory in Design, marzec 2015, © Philip Treacy and Clare Farrow, 2015.

Childhood ReCollections of Philip Treacy

Clare Farrow in conversation with Philip Treacy

Editor: Jansson J. Antmann

In the second of our Childhood ReCollections this issue, we leave the world of architecture to gain an insight into the early inspirations of legendary hat designer Philip Treacy. Like Zaha Hadid, Daniel Libeskind and Kengo Kuma, whom we have already met in this series, writer and curator Clare Farrow interviewed Treacy in preparation for her exhibition, Childhood ReCollections: Memory in Design, which opened at the Roca London Gallery last year. Of the six designers featured, five were architects. However, inspired by Chanel’s words – ”Fashion is architecture: it is a matter of proportions” – Farrow extended the theme of the exhibition beyond architecture and furniture design into the world of fashion. We first encountered references to fashion when Daniel Libeskind recalled his mother’s geometric, structured designs for women’s underwear. Now we embrace it fully in the inspirational form of hat designer Philip Treacy, whose childhood memories also encompass light, colour, nature, scent, materials, structure, and above all, a heightened sensitivity to the world.

The son of a baker and second youngest of eight children, Philip Treacy was born in 1967 in Ahascragh, County Galway. There is scarce mention of this tiny Irish village in the history annals, and such humble beginnings seem at odds with a career that would see him design for a range of clients ranging from the British Royal Family and the Royal Ballet, to Lady Gaga and the ‘Harry Potter’ film franchise. His first experiments in design were in handling the feathers of his mother’s chickens, ducks, and pheasants, and making clothes for his sister’s dolls with a sewing machine that he was not supposed to touch. He left home for Dublin to study at the National College of Art and Design, before winning a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in London in 1988. Still a student, it was during a 1989 photo shoot for Tatler, that he met the magazine’s style editor, Isabella Blow, who had also discovered and invested in Alexander McQueen’s first collection. Soon Treacy was designing hats for Karl Lagerfeld at Chanel. After his graduation show in 1990, he opened his eponymous studio in London and entered into celebrated collaborations with many fashion houses, including Givenchy, Valentino and Alexander McQueen. Awarded an honorary Order of the British Empire in 2007, it was a far cry from the small village of about 500 people in which he’d grown up and everybody knew everybody.

“My world seemed so fascinating, but my perception of the outside world was coloured in by my sister and brothers. As they grew up, they moved to London, and so London was Camelot to me.”

As a child in the 70’s, Treacy lived across the road from the church and it had a profound influence on his aesthetic sense. He loved watching brides arrive in their exotic wedding dresses and he attended every single wedding, uninvited.

“When the bride appeared, I just couldn’t believe it. That was my whole perception of fashion. […] I didn’t really tune into hats much at that point; it was more the fantasy moment. Then I would collect all the confetti after the people had gone.

My idea of beauty as a child was the exceptional, like a fantastic movie, or the church. All the colours that I use are really the Catholic church colours: the deep pink of the priest’s vestments, or pale blue; all my colour sense is very religious colours, beautiful damask golds. I’m still designing for the Madonna [of the church].”

Breaking through boundaries and stereotypes seemed to come naturally to Treacy, and he seemed to find support in all the right places, including at school.

“[…] I noticed that the girls did sewing at a certain time of the day the boys did not. When you’re 6, you don’t really have any inhibitions, so I asked the teacher if I could do that too, […] and she decided, ‘Okay!’ So she taught me to sew. After that, she taught all the boys to sew.

[…] I remember distinctly one day, one of our neighbours saying to my father, ‘Don’t you think it’s strange that your son is making dresses for dolls?’ and I overheard my father saying, ‘Whatever makes him happy’, which was incredible.

[…] Growing up in a large family, you learn that everybody’s different; everybody is accommodated. It’s a very good lesson in life. But also in Ireland, people’s idiosyncrasies in small villages were accepted. […] You think it’s about the place, but the place is still there. What made it special were the people.”

His earliest memories of a very simple beret that his mother wore, formed the basis of his approach to designing hats today.

“I always remember distinctly […] wondering why the positioning of the hat was important to her, because she spent a period of time arranging the hat, so it wasn’t just thrown on. […] She was making the hat work with her face and her hair. It was a very simple hat, but it was always considered.”

Treacy loves making beautiful things and experimenting with new shapes. It is fundamental to who he is.

“The physicality of creating, from a two-dimensional material to a three dimensional material, has always been with me, because I always like to make something out of nothing. I still do. […] If you’re making a cake or bread, or clothes, or hats, or jewellery, it’s something amazing: the satisfaction in making beautiful things, or doing something to the best of your ability, is what it means to be human.”

In pursuit of this, the nature and materials that surrounded him, such as the flowers and birds in his garden, are still a source of inspiration.

“I would imitate nature in materials. So I would try to make leaves and figure out that by burning with a candle the edge of cheap polyester material, it crinkles and burns and looks like the edge of a leaf.

I was always fascinated by feathers, because I thought that they were the most incredible material, […] a feather is a membrane, it has a weightlessness, a transparency; it’s like a living, breathing material; it’s unlike any other material, and it’s got magic. One of the first hats I made with feathers from my mother’s chickens, went to Ascot!”

Like the architect Kengo Kuma, Treacy also sees natural materials as an antidote to the concrete world of today.

“As we become more citified, we need more gardens, flowers, to remind us that it isn’t just concrete. When you’ve worked in fashion for 23 years you realize that luxury is not about a Louis Vuitton handbag at all. Nature is luxury. Birdsong is luxury. Imagination is luxury.” |

The extracts / quotes are all from an interview by Clare Farrow for Childhood ReCollections: Memory in Design, March 2015, © Philip Treacy and Clare Farrow, 2015.