![]()

POKAŻ MI SWOJE OBRAZY

Artysta digital culture, z której czerpie inspiracje budując swój przekaz.

Ale często z przyjemnością zanurza się w minione czasy. Rozmawiam

z Piotrem Krzymowskim – absolwentem Central Saint Martins w Londynie.

TEKST: BEATA BRZESKA

Nadal nie lubisz, kiedy nazywa się ciebie artystą?

Już polubiłem (śmiech), chociaż nadal uważam, że artysta jest określeniem bardzo schematycznym. Kiedy mówię, że jestem artystą, natychmiast pada: O, to pokaż mi swoje obrazy. Większość ludzi utożsamia pojęcie artysty z rzemieślnikiem, z kimś kto ma konkretny warsztat, umiejętności. Dla mnie sztuka to obserwowanie rzeczywistości i tłumaczenie tego na swój własny język, który nie zawsze jest oczywisty i od razu zrozumiały.

Poduszka emoji wypełniona ręcznie pisanymi listami miłosnymi z 1920 roku, 2018 r.

Czy to znak czasu, że sztuka wyszła z muzeów, sal wystawowych? Czy ma jeszcze znaczenie, co nazywamy sztuką?

Z jednej strony mamy cały sztab kuratorów, galerzystów, historyków sztuki, którzy określają, co jest sztuką, a co nią nie jest. Z drugiej strony żyjemy w czasach mediów społecznościowych, gdzie każdy może zaprezentować siebie, nazwać siebie światowej sławy

fotografem, fit-influencerem, czy stylowym guru. Media społecznościowe zdemokratyzowały w konsekwencji również świat sztuki. Ale gdyby jutro zniknął Instagram, to cały czas mielibyśmy sztukę. Influencerów już pewnie nie.

Twoje prace są związane z cyfrową kulturą i mocno osadzone w tej rzeczywistości. Czy obserwujesz świat jak naukowiec np. socjolog, czy go komentujesz?

I jedno i drugie. Zwracam uwagę na rzeczy, których często nie zauważamy i które pomijamy. Na przykład w pracy video Wyszukiwarki, pokazuję autouzupełnienia haseł wpisywanych do największych wyszukiwarek w internecie. Pomijamy je, a tymczasem dzięki nim można dotrzeć do tego, co siedzi w naszych głowach. Zanim idziemy do lekarza, szukamy pomocy w Google. Internet przez to wie o nas wszystko. Zna nasze pragnienia, lęki, fetysze. Z drugiej strony koncentruje się na rzeczach, które są mniej zauważalne, ale mają bardzo rzeczywisty aspekt i wymiar. Jedną z instalacji, którą będę chciał pokazać w CSW w Toruniu podczas mojej następnej wystawy, będzie ciąg starych linijek zawieszonych

na „średniej” wysokości wzroku. Linia odmierzać będzie dokładnie 26 metrów, bo tyle średnio nasze palce codziennie „pokonują” na ekranach telefonów, przewijając zdjęcia lub posty.

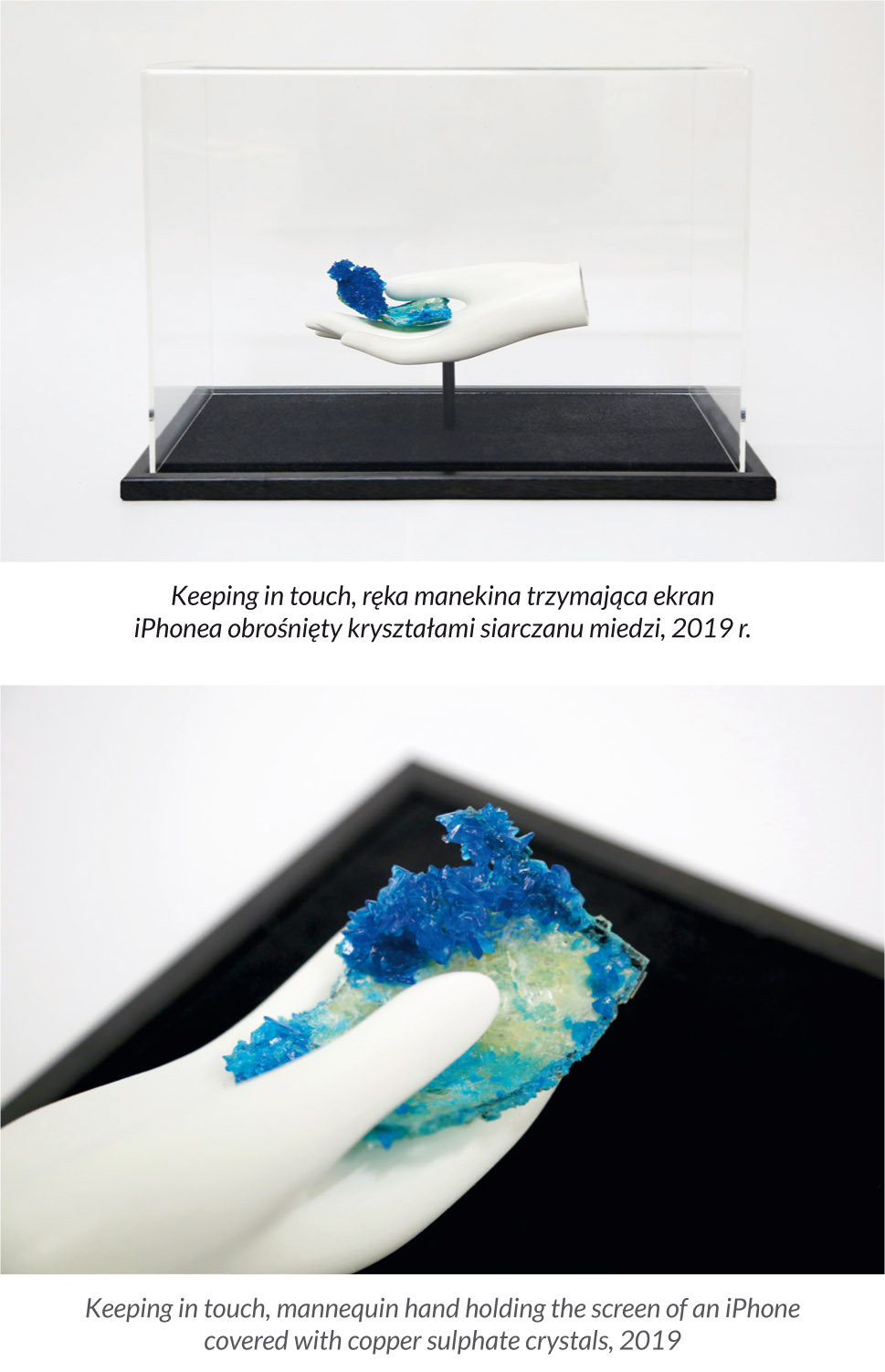

Tematem twoich prac jest też człowiek i jego ciało. A touch too much, Keeping in touch to sensualność w zderzeniu z technologią.

Tak. Przypominam o naszej cielesności i delikatności. A touch too much to sitodruk ukazujący odciski palców zebrane z ekranu mojego telefonu po jednym dniu jego używania. Praca powstała, kiedy dowiedziałem się, że średnio codziennie dotykamy naszego telefonu 5600 razy. Nie zauważamy w jak intymnej relacji jesteśmy z własnym telefonem! Nawet siebie nie dotykamy tak często. Jesteśmy tak bardzo skupieni na wykorzystywaniu wzroku, że zapominamy o reszcie zmysłów, przede wszystkim dotyku. Z kolei rzeźba Keeping in touch to dłoń manekina trzymająca szklany ekran smartfona obrośnięty kryształami siarczanu miedzi. Dzięki tej substancji chemicznej możemy korzystać z elektroniki.

I choć małe ilości siarczanu są nieszkodliwe, to w dużych stają się śmiertelnie niebezpieczne. Praca w związku z tym przypomina zarówno o kruchości technologii, jak i wrażliwości naszych ciał.

Bardzo to wieloznaczne myślenie.

Chcę pokazywać to, co nas otacza, a co jest niezauważalne, gdzieś pod powierzchnią współczesności. Czasem w zabawny, czasem w zaskakujący sposób chcę dotrzeć do głębszych warstw naszej rzeczywistości. Nie oceniam, nie mówię, co jest lepsze, a co

gorsze. Sztuka musi być niejednoznaczna, poddająca się interpretacjom, elastyczna. Uruchamiająca myślenie i wyobraźnię.

Podobnie jak w cyklu prac z emotikonami.

Emotional Buggage to instalacja złożona z poduszek emoji upchanych w próżniowej torbie. Są pomarszczone, bardziej trójwymiarowe i niedoskonałe – w przeciwieństwie do idealnie okrągłych i lśniących ikonek emocji w telefonach. Tytuły powstały przy pomocy internetowego tłumacza, który zamienia zdanie złożone z emoji na tekst. Tłumaczenia nie mają za wiele sensu – opierają się na algorytmie. Ale samo istnienie takiego tłumacza świadczy o tym, jak ważnym językiem są emotikony. Według statystyk,

używamy ich średnio 60 milionów razy dziennie w mediach społecznościowych i ponad 5 miliardów razy w aplikacji Messenger. W cyklu tych prac jest też półprzezroczysta poduszka emoji zbuziaczkiem. Widać w niej ręcznie pisane listy miłosne z lat 20., które znalazłem na targu staroci w Londynie. Porównuję język komunikacji teraz i przed 100 laty.

Korzystasz z wielu środków wyrazu: wideo, instalacje, fotografia, kolaże. I to się stale zmienia.

Zaczynałem od filmu, robiłem kolaże. To jest naturalny rozwój, a język wyrażania się wynika z moich poszczególnych zainteresowań. Kiedy zafascynowałem się wyszukiwarkami, idealnym medium było wideo. Kolaże przestałem ciąć bo, pomimo mojej pasji do kina lat 60., głównie francuskiej Nowej Fali (Godard, Truffaut – to dla mnie geniusze, jeśli chodzi o plastyczność, innowacje w narracji, itd.), doszedłem do wniosku, że to zainteresowanie w ogóle nie odzwierciedla w żaden sposób dzisiejszości. Jest dekoracyjne. I tyle.

Zawsze chciałeś być artystą? Dlaczego artystą po Saint Martins?

Dostałem się do ASP na Wydział Wzornictwa i do Saint Martins na rok zerowy, po którym trzeba wybrać ścieżkę edukacji. Zaryzykowałem, pojechałem do Londynu i wybrałem kierunek pod intrygująco brzmiącą nazwą 4D. To dyscyplina mediów związanych z czasem,

ponadwymiarowością, czyli film, wideo, dźwięk. A wybrałem Saint Martins, bo wiedziałem, że tam trzeba zaprezentować siebie, ceni się kreatywność i nie ogranicza.

Czy twoje prace zobaczymy w tym roku w Polsce?

Na pewno w CSW w Toruniu w drugiej połowie roku. Zapraszam też do Londynu do galerii Roman Road. Oba miejsca łączy… fundacja ZW, której jestem członkiem, zajmująca się między innymi archiwizacją prac Natalii LL, polskiej artystki intermedialnej, konceptualistki.

O tym, co pokażę, nie będę opowiadał. I tak już się rozgadałem o instalacji dla CSW (śmiech). Zapraszam na wystawy.|

![]()

CAN I SEE YOUR PAINTINGS PLEASE?

He is an artist made truly in the digital culture. And that’s exactly where his main

inspiration and drive come from. Nevertheless, he often travels in time in order

to draw parallels with the brutal present. I am interviewing Piotr Krzymowski

– a graduate of the infamous Central Saint Martins in London.

TEXT: BEATA BRZESKA

Do you still dislike being called an artist?

I actually started liking it a lot! (laughs). Sorry, I must have ruined your plan. I got used to it, though I’m still convinced that the word artist is extremely conventional and boring. When I tell people what I do, they immediately reply saying: “That’s wonderful! Can I see

your paintings please?”. Most of us picture artists as craftsmen – people with particular skills and talents. Just like painters for example. For me though, being an artist is based on observing the contemporary world around and translating it to an individual language, one

that is not always immediately obvious and absorbing.

Is it a milestone that the art is leaving the spaces of museums and galleries today? Does it still matter what we name as “art”?

On one hand we have a group of curators, gallerists and art historians, who define what is art, and what isn’t. On the other hand, we encounter the era of omnipresent social media, which allow us to represent ourselves and therefore call ourselves world-class photographers, fit-influencers, models, or style gurus. Platforms like Instagram have in consequence also democratized the art world. Nevertheless, if Instagram disappears tomorrow, we will still thank God have art. The faith wouldn’t be so kind to the influencers

though.

Your works are very much related to our digital culture and seem to be rooted heavily in the reality of that kind. Do you observe the world as the sociologist for instance or do you only comment on it?

Both (laughs). I tend to focus on those aspects of the everyday, which we often miss or abandon. For example, the video work Search Engines, which I showed at the CoCA in Torun last year, presents the automated search suggestions for the sentences we put into the largest internet search engines. We tend to ignore these engines, but they prove to be rather useful as we can learn a whole lot of things about ourselves from them. Before we decide to see a doctor, we analyse the symptoms via Google. Therefore, the internet knows

absolutely everything about us. The Big Brother knows our desires, fears and fetishes. I also tend to pay a lot of attention to things that are less noticeable but have an extremely real quality and dimension. One of the art installations, which I’m planning to show during my next solo show at the CoCA in Torun will be a line formed of old rulers, which will be hanging at an average eye sight height. The line will be measuring exactly 26 metres,

which is a distance that the average smartphone user travels on the screen of his iPhone whilst scrolling through images and data.

One of the themes you seem to be also interested in is the human being and his body. A touch too much, keeping in touchare the works dealing with both sensuality and technology.

Absolutely. In my works I often refer to our physicality and it’s fragility. A touch too muchis a screen print illustrating the fingerprints collected from the screen of my iPhone after using it for the period of 24 hours. This particular work was created after I learned that on

average we touch the screen of our devices at least 5600 times a day. Forget about the hygiene, but it’s a rather intimate relationship we have with our phone! I don’t even touch myself that often. I wish I did! (laughs). The thing is that we are focused so much on using our sight when we use the smartphones that we totally ignore the rest of our senses, and most importantly the sense of touch. That brings us to another work named keeping in touch, which features a mannequin hand holding the screen of my ex-iPhone, which is now covered with copper sulphate crystals (and by the way is embedded with my own

fingerprints). The important aspect of this work is that the aforementioned chemical substance is used in the production of all of our everyday electrical devices, but is also extremely harmful in large quantities. The work then reminds us about not only the fragility of technology, but also one of our own bodies.

It sounds multi-layered and provokes one to think.

I really desire to showcase what is around us, but what is not immediately noticeable as is hiding underneath the layer of contemporaneity. Sometimes I’m using humour to accentuate it, sometimes an element of surprise. I don’t want to judge, or point towards the good or the bad. In my opinion art should not present crafted judgments. It should instead offer a space for interpretation and reflection. It should provoke one to think and dream.

That sounds just like your other series of works featuring the emoji icons.

Emotional Baggageis an art installation constructed of the emoji pillows stuffed inside storage, vacuum bags. The pressure used in the process of making the work allowed these pillows to gain a human quality – they are wrinkled, more three-dimensional and imperfect – in contrast to the perfectly round and glossy icons displayed on the screens of our smartphones. The titles of individual works though came from the online translator, which converts a sentence constructed with the emoji icons into text. Even though the results don’t make much sense due to the algorithmic structure of the translator, it’s presence proves that emojis are a fast growing language that is taken seriously. According to the statistics, we use 60 million emoticons daily on social media platforms and over 5 billion of them on Messenger. There is another work in the series worth mentioning here. It’s the emoji pillow, which had the back replaced with a transparent fabric. It exposes the new stuffing of the cushion – hand-written love letters from the 1920’s. I found them on a flee

market in London. The work compares the language of expressing love today and a hundred years ago.

You tend to use many forms of expression: video, art-installation, photography, and collage. And you are consistent in this inconsistence of forms.

As a student I started with film and making collage, both of which are based on the process of montage. For me to change forms of expression is a natural development.

The language of expression for me results from particular interests. When I was totally obsessed with the search engines I realised that the ideal form to express and document that was video. I should mention here that many remember me as a collagist. I don’t use this technique as often these days, despite my obsession with the films of Godard and Truffaut from the 60’s (which triggered the interest in collage). I came to the conclusion

that this interest doesn’t reflect on the contemporary everyday anymore. The collage works I made were decorative. That’s it.

Did you always dream of being an artist? And why one graduating from Saint Martins?

I was never a child that one would find sitting in the corner of a room with an inseparable pencil in his hand or nonstop dragging his parents to the museums. It started rather late, and as a teenager I happened to be accepted both to the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw and to Central Saint Martins in London. I took a risk and went abroad eventually choosing the intriguingly sounding degree of 4d. It’s a course focusing on the disciplines related to time such as film, video, or sound. Why did I choose Central Saint Martins? I knew that I could truly express myself in order to get in, rather than showing off with my skills. This academy in London particularly values the creativity more than the skills.

Can we see your works in Poland this year?

I will have a solo presentation at the Centre of Contemporary Arts in Torun later this year. I would also love you to see a group show at the Roman Gallery coming up in few months. Both places are related to the ZW Foundation. I’m pleased to be the chairman of the foundations’ council. The important part of the organisation is the Archive of Natalia LL – Polish female artist, who gained an exquisite recognition in the last century. I won’t tell you about the works I will be showing, I already shared some secrets (laughing). Come and see. |

Bardzo ciekawy artykuł i bardzo interesujący artysta! Brawo!

Świetny wywiad! Gdzie można przeczytać całość?