![]()

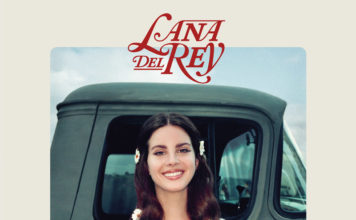

24-letni Jan Lisiecki jest jednym z najwybitniejszych współczesnych pianistów na świecie. Współpracował z tak uznanymi dyrygentami, jak Claudio Abbado, Sir Antonio Pappano, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Daniel Harding i Pinchas Zukerman. Podpisał ekskluzywny kontrakt z Deutsche Grammophon i jest stałym gościem Festiwalu Chopin i jego Europa. Obecnie koncertuje po całym świecie z Australian Youth Orchestra pod batutą Maestro Krzysztofa Urbańskiego. Rozmawiamy z Janem Lisieckim w Pekinie, przed jego debiutem w Sydney Opera House.

Tekst: Jansson J. Antmann

Zdjęcia: Christoph Köstlin / Holger Hage

Zdjęcia dzięki uprzejmości Deutsche Grammophon

Jaki jest twój typowy dzień?

Dzisiaj nie mam zamiaru wykonywać żadnej pracy ani ćwiczyć. Zamierzam odwiedzić Pałac Letni w Pekinie i kilka innych miejsc, w których nigdy nie byłem. Podczas tej trasy, w zwykły dzień występu, wstawałem o 6 rano, jadłem szybkie śniadanie, następnie brałem taksówkę, potem jechałem pociągiem przez 4 godziny, ćwiczyłem przez dwie godziny, udzielałem wywiadu, a następnie występowałem na koncercie o 20.00. Tak było przez kilka ostatnich tras przed przybyciem do Chin. Występowaliśmy w Amsterdamie w Concertgebouw, potem w Wiesbaden w Kurhaus, gdzie nagraliśmy koncert do wydań audio i wideo; a następnie w Kassel w Kongress Palais. Generalnie jestem bardzo energiczny i wydaje mi się, że nie umiem odpoczywać bez powodu. Co więcej, jestem bardzo ciekawy wszystkiego, więc nigdy nie zwalniam. Zawsze będę przekraczać granice i cieszyć się każdą chwilą dnia nawet, gdy występuję. W przeciwnym razie, gdybym nigdy nie opuszczał mojego pokoju hotelowego, nie byłbym zadowolony z odwiedzenia wszystkich tych niesamowitych miejsc na całym świecie.

Pierwszy koncert na festiwalu Chopin i jego Europa prawie się nie wydarzył, prawda?

Miałem wtedy 13 lub 14 lat. Moja kariera nie zaczęła się od huku. Nie był to wynik wygranej w konkursie ani znajomości właściwych ludzi. Nie urodziłem się w muzycznej rodzinie, nie uczyłem się u „najlepszego” profesora, nie chodziłem do „najlepszej” szkoły… więc pomysł wyjazdu do Warszawy nie był mój. To był pomysł Howarda Shelleya. Słyszał jak gram na konkursie pianistycznym w Manchesterze. Nagrodą była możliwość występu w Katedrze w Manchesterze, i to był powód, dla którego wziąłem udział w konkursie. nie chodziło o wygraną, ale o możliwość występu z orkiestrą w tej przepastnej przestrzeni. Howardowi spodobał się sposób, w jaki grałem Koncert Chopina i pomyślał, że byłoby idealnie, gdybym wystąpił na Festiwalu Chopinowskim w Warszawie. Początkowo organizatorzy wahali się, powiedzieli Howardowi, że to nie jest scena przeznaczona dla cudownych dzieci, i uprzejmie mi odmówili, zasłaniając się budżetem. Nie byłem zirytowany. Wspomniałem Howardowi, że ponieważ i tak będę w Polsce, odwiedzając moich dziadków w Gdańsku i Poznaniu, zamierzam przyjść na jego występ na festiwalu. Howard natychmiast osaczył organizatorów, mówiąc, że skoro nie musieli płacić za moje bilety lotnicze nie ma powodu, aby nie włączyć mnie do programu. I zdarzyło się, że wystąpiłem. Po moim pierwszym występie natychmiast zaprosili mnie na następny rok i od tego czasu grałem tam ponad 10 razy. Mam wieloletnie i cenne relacje z festiwalem. Otwarte dla mnie drzwi w Europie, nie otworzyłyby się przez wiele lat, jeśli w ogóle, gdyby nie Festiwal Chopin i jego Europa oraz Instytut Chopina.

Czy kiedykolwiek myślałeś, co by było, gdyby te drzwi nie zostały dla ciebie otwarte?

Nie lubię myśleć o tym, co mogło być. [śmiech] Kiedy patrzysz na moje dotychczasowe życie i próbujesz rozwikłać splątaną sieć – skąd pochodzę, gdzie jestem i jak się tu dostałem – bardzo trudno jest określić, które momenty i decyzje miały decydujący wpływ. Myślę, że w pewnym sensie, wszystkie są ze sobą powiązane, więc trudno wyobrazić sobie alternatywny scenariusz.

Powiedziałeś, że kiedy grasz utwór, to grasz, żeby podkreślić, jak pięknie został napisany, a nie po to, żeby podkreślić, jak ty pięknie grasz. Czy jedno nie wiąże się z drugim?

To jedno z najbardziej fundamentalnych pytań, ponieważ interpretując odciskamy swój ślad na dziele sztuki. Osobiście uwielbiam być sługą muzyki i czerpię największą inspirację z partytury i tego, co mi przedstawia. Moim obowiązkiem jest reprezentowanie utworu w jak najlepszym świetle. Dla mnie geniusz naprawdę leży po stronie kompozytora. Oczywiście czy mi się to podoba, czy nie, na scenie reprezentuję siebie na wiele sposobów, ale staram się nigdy nie stawać przed muzyką. Gdybym kiedykolwiek to zrobił, byłbym bardzo zniechęcony i próbował coś zmienić, ponieważ nie dlatego robię to, co robię. Nie używam muzyki do autopromocji, ale raczej jestem na scenie z powodu muzyki. Może to zabrzmieć trochę altruistycznie, ale w końcu to prawda.

Pracowałeś z najlepszymi dyrygentami i orkiestrami na całym świecie. W tym roku współpracowałeś z Orpheus Chamber Orchestra i nagrałeś płytę Mendelssohn. Mówiłeś, jak niesamowitym i wyjątkowym doświadczeniem była praca bez dyrygenta, przy czym wszyscy muzycy wzajemnie dawali sobie wskazówki. Wolisz teraz pracować z dyrygentem czy bez niego?

Po tym nagraniu występowałem z Orpheus Chamber Orchestra podczas długiej trasy koncertowej, i po tych wszystkich wywiadach zdałem sobie sprawę, dlaczego tak bardzo lubię z nimi współpracować. Chodzi o poświęcenie każdej osoby – bez ego, skupienie się na muzyce, a nie na własnych celach – co nie jest powszechne. Współpraca z artystami, którzy są tylko po to, by służyć muzyce, to taka sama przyjemność, jak praca z dyrygentami, którzy są pasjonatami tego, co robią, bez względu na ich imię, nazwisko, reputację. Odkładając to na bok, istnieje zupełnie inny wymiar niż praca z dyrygentem lub bez niego. W rzeczywistości podczas obecnej trasy z Australian youth Orchestra zagraliśmy I Koncert fortepianowy Mendelssohna, a także II Koncert fortepianowy rachmaninowa, który gramy w Chinach i Sydney. Z Orpheus Chamber Orchestra było tak blisko i intymnie – tak niewiele słów trzeba było wypowiedzieć. Z pewnością tracisz trochę swobody podczas pracy z dyrygentem, ale czasem musisz się zastanowić, czy ta wolność jest tak ważna. Robisz to z jakiegoś powodu, czy po prostu jesteś przyzwyczajony do grania w określony sposób? Myślę, że czasami absolutny magnetyzm muzyków, którzy zwracają tak dużą uwagę na to, co robisz, nie ma sobie równych. Jednak w innych przypadkach, dyrygent może zainspirować orkiestrę w taki sposób, że sam nie byłbym w stanie tego zrobić.

Jak to jest pracować z Krzysztofem Urbańskim?

Absolutnie uwielbiam Krzysztofa. Jest jednym z dyrygentów orkiestry, z którymi najbardziej lubię pracować, ponieważ jest niesamowicie skupiony i oddany. Oczywiste jest, że to świetny muzyk i świetny technik, ale jest także miłą osobą zarówno na scenie, jak i poza nią. Jest pasjonatem muzyki bez szaleństwa i z przyjemnością rozmawiamy o wszystkim. To dla mnie ważne, ponieważ lubię ludzi wszechstronnych. Krzysztof jest nie tylko świetnym dyrygentem, ale także uroczą osobą, z którą lubię spędzać czas.

Rozmawiacie po polsku czy po angielsku?

Mówimy po polsku. W Amsterdamie zapytano nas, czy to przyczyniło się do naszej przyjaźni. Nie sądzę, żeby nasze relacje były zasadniczo inne, gdybym nie mówił po polsku. Możemy równie łatwo komunikować się w języku angielskim i nie wydaje mi się, żeby wspólny język zmienił wymiar naszej przyjaźni czy tworzenia muzyki. Trudno mi uwierzyć, że krew lub DNA wpływa na to, jak grasz muzykę. Moi ulubieni wykonawcy muzyki Chopina niekoniecznie są Polakami. Oczywiście jest Krystian Zimerman – Polak, którego absolutnie uwielbiam, ale jest też Martha Argerich, Maria João Pires czy Maurizio Pollini – ludzie, którzy mają bardzo mało lub wcale nie mają nic wspólnego z Polską, a mimo to grają Chopina w wybitny sposób. Tożsamość kulturowa jest ważna i kształtuje to, kim jesteś, ale niekoniecznie jest niezbędna do odtwarzania muzyki w określony sposób.

Jak zachować świeżość, grając dany utwór wiele razy?

To jest bardzo łatwe. Zawsze coś mnie inspiruje. W przypadku koncertu inspiruję się pomysłami orkiestry i dyrygenta, i je wdrażam. Jeśli to recital, zawsze coś kształtuję i zmieniam. Po prostu pracuję trochę nad kawałkiem, aby odkryć źródło mojej inspiracji. Innym powodem, dla którego nigdy się nie nudzę, jest to, że moja interpretacja ciągle się zmienia. Lubię odkrywać nowe możliwości. Oczywiście wszyscy mamy swoje unikalne cechy osobowości i styl, które przenikają naszą pracę. Nie możesz całkowicie zmienić sposobu interpretacji utworu, ale zawsze pojawiają się nowe pomysły i przemyślenia, a ja jestem na nie bardzo otwarty.

Teraz koncertujesz z Australian Youth Orchestra. Jak ważna jest edukacja muzyczna dla młodych ludzi?

Niezwykle ważna, nie ma sobie równych. Nawet jeśli nie prowadzi do kariery muzycznej, to uczy wielu umiejętności życiowych, a przede wszystkim, uczy doceniania sztuki wyższej. W społeczeństwie, w którym tak łatwo być przytłoczonym tymi wszystkimi mediami i tak zwaną „wiedzą”, nieocenione jest posiadanie czegoś starego i tradycyjnego, czegoś, co wymaga czasu na zrozumienie. Muzyka klasyczna nie jest czymś, co można po prostu odebrać i zrozumieć w ciągu jednego dnia. Dla wielu osób stanowi to poważną barierę. Kiedy jednak odniesiesz sukces w ocenianiu siebie i w zrozumieniu muzyki, to myślę, że jest to bardzo satysfakcjonujące. Jeśli mówimy o edukacji muzycznej na poziomie zawodowym i o tym, co robi Australian Youth Orchestra, niezwykle ważne jest, aby młodzi muzycy mieli kontakt z każdym aspektem tego doświadczenia. Przede wszystkim jest to doświadczenie orkiestrowe, które pozwala odkryć rzeczy, których nigdy nie mogliby się nauczyć u nauczyciela muzyki w studio. Potem jest kwestia bycia w trasie, co muszę przyznać, według moich standardów i tego, czego doświadczyłem z dużymi orkiestrami na całym świecie, jest raczej luźne. To znaczy, że dzień wolny, jak na przykład dzisiaj w Pekinie, jest luksusem i ogromnym wydatkiem na typową orkiestrową trasę koncertową. Niemniej muzycy wiedzą, jak to jest koncertować z orkiestrą, a widzę, że dla niektórych jest to już dość trudne. Daje im to możliwość przekonania się, czy poradzą sobie z napiętym harmonogramem, zanim zdecydują się na uczestnictwo w ciągłych konkursach, stałe poszerzanie repertuaru i życie w trasie. Doświadczenie bycia razem w trasie to coś, czego nie można wyjaśnić w żaden sposób. Zabrzmiało to dramatycznie, ale wielu uwielbia to robić i przekonuje się, że to ich inspiruje, że to ich życie. Spójrz na mnie! Uwielbiam podróżować, więc świetnie się to łączy z moją karierą pianisty koncertowego.

Co podczas tej trasy skłoniło ciebie i Krzysztofa do dołączenia do Australian Youth Orchestra?

Ma świetną reputację i jest dowodem niesamowitej pracy młodych muzyków, jaką wykonali przez lata. Krzysztof i ja współpracowaliśmy z wieloma orkiestrami najwyższej klasy. na przykład Schleswig-Holstein Musik Festival ma podobną orkiestrę młodzieżową i mieliśmy z nimi wspaniałe doświadczenia. Nie mamy nic przeciwko próbom. Przeciwnie, chętnie pracujemy nad rzeczami, które lubimy. Atmosfera może być czasami bardzo zrelaksowana i przyjemna, jak w przypadku Australian Youth Orchestra. Zawsze cieszę się na ponowne spotkanie.

Czy różnorodna kulturowo orkiestra młodzieżowa może być panaceum na problemy na świecie?

Nie tylko orkiestra młodzieżowa. Powiedziałbym, że to muzyka. Muzyka zawsze jakoś przetrwała. Bez względu na zakres ludzkiego cierpienia piękna muzyka zawsze była pisana i wykonywana. To powinno być dla nas inspiracją i przypominać, jak odporni jesteśmy, jako ludzie. Jako muzyk nie chcę nigdy wypowiadać się na tematy polityczne, ponieważ chcę, aby muzyka jednoczyła ludzi. W sali koncertowej jest coś jednoczącego w tworzeniu wspaniałej sztuki, którą wszyscy kochamy i lubimy. Upolitycznienie wykorzystywałoby twórczość Mozarta, Beethovena, Chopina. Można powiedzieć, że wszyscy mieli jakiś program polityczny, ale ostatecznie powinniśmy służyć większemu dobru, zamiast polaryzować, i tak coraz bardziej podzielony, świat. Uważam ten podział za przerażający, ale widzę, że publiczność i muzycy, którzy niekoniecznie mają takie same poglądy polityczne, bardzo dobrze się dogadują w sali koncertowej. Zachowajmy to w ten sposób – jako sanktuarium. |

Jakie jest twoje ulubione danie, które przygotowujesz, kiedy wracasz do domu?

Muszę być szczery i powiedzieć, że nie gotuję. I nie jestem smakoszem, jak wiele innych osób. Powiedziawszy to, przyznam jednak, że ilekroć odwiedzam dziadków w Polsce, mam takie miejsce, do którego lubię chodzić na sznycel ze szczególną panierką, ziemniakami i marynowaną sałatką z ogórków, popularną w Poznaniu. Więc tak, za każdym razem, gdy ich odwiedzam, idziemy tam na piwo i sznycel. To jest coś, na co zawsze czekam.

Najnowsza płyta Jana Lisieckiego, wydana przez hamburski Deutsche Grammophon, już od 13 września w sprzedaży.

To Serve Music

24-year-old Jan Lisiecki is one of the most outstanding pianists in the world today. He has worked with such conductors as Claudio Abbado, Antonio Pappano, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Daniel Harding and Pinchas Zukerman. Lisiecki signed an exclusive contract with Deutsche Grammophon and he is a regular guest at the Chopin and his Europe festival. He is currently touring the world with the Australian Youth Orchestra under the baton of Maestro Krzysztof Urbański. We talk to Lisiecki in Beijing, ahead of his debut at the Sydney Opera House.

Text: Jansson J. Antmann

Photos: Christoph Köstlin / Holger Hage

Photos courtesy of Deutsche Grammophon

What’s a typical day like for you?

Today I have no intention of doing any work or practising. I intend to visit the Summer Palace in Beijing and a few other places I’ve never been. During this tour, a regular performance day would see me get up at 6am, have a quick breakfast and then take a taxi, go by train for 4 hours, rehearse for two, give an interview and then perform at the concert at 8pm. It was like that for the last few dates of the tour before arriving in China. We performed in Amsterdam at the Concertgebouw; then in Wiesbaden at the Kurhaus where we recorded the concert for audio and video release; and then in Kassel at the Kongress Palais. I’m generally a very wound-up kind of person, in the sense that I’m very energetic and can’t seem to find it in me to relax without a reason. On top of that, I’m very curious, so I never take it easy. I will always push the limits and enjoy every moment of every day, even when I’m performing, otherwise I would feel quite unhappy about visiting all these amazing places around the world, if I never left my hotel room.

Your first concert at the Chopin and His Europe Festival almost didn’t happen?

I was 13 or 14 at the time. My career didn’t start off with a bang. It wasn’t the result of winning a competition or having the right connections. I wasn’t born into a musical family; I didn’t study with the 'best’ professor; I didn’t go to the 'best’ school … so the idea of going to Warsaw wasn’t mine at all. It was Howard Shelley’s. He’d heard me playing at a competition in Manchester. The prize was the opportunity to perform at the Manchester Cathedral, which was the whole reason I entered the competition. It wasn’t about winning, but about the opportunity to perform with an orchestra in that cavernous space. Howard liked the way I played the Chopin concerto and he thought it would be perfect to perform at the Chopin Festival in Warsaw. At first the festival organisers were hesitant and told Howard that it wasn’t a platform for child prodigies and politely turned me down on the basis that I wasn’t in the budget. I wasn’t fazed and mentioned to Howard that I was going to come to hear him perform at the festival anyway, since I was going to be in Poland visiting my grandparents in Gdansk and Poznan. Howard immediately cornered the festival organisers by saying that since they didn’t need to pay for my airfares, there was no reason not to include me in the program and I ended up performing after all. After my first appearance, they immediately invited me back and since then I’ve played there over 10 times. It’s a longstanding and cherished relationship because I would say that in many ways the doors that were opened for me in Europe by the Chopin and His Europe Festival and the Chopin Institute would not have been opened for many years, if at all.

Have you ever thought what might have been if those doors hadn’t been opened for you?

I don’t like what-ifs. [laughs] When you look at my life so far and try to untangle the web of where I’ve come from, where I am, and I how got here, it’s very difficult to identify which moments and decisions made a crucial difference. In a way, I think they’re all interwoven so it’s hard to imagine an alternative scenario.

You’ve said that when you play a piece, you play to highlight how beautifully it was written and not necessarily how beautifully you play. Doesn’t one predicate the other?

That’s one of the most fundamental questions of interpretation because, in the end, that’s where we come to make a piece our own. I personally love to serve the music and I find most inspiration within the score and what I’m presented with. My responsibility is to represent it in the best possible light. For me, the genius truly lies within the composer’s reins. Of course, I’m the one on stage and, whether I like it or not, I’m representing myself in many ways, but I try never to put myself before the music. If I’d ever do that, I’d be very disheartened and I’d try to change things, because that’s not why I do what I do. I’m not using the music as a means of self-promotion, but rather I am on stage because of music. It may sound a little altruistic, but it’s true in the end.

You’ve worked with some of the greatest conductors and orchestras around the world. This year you worked with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra and recorded an album of Mendelssohn. At the time you talked about what an incredible and unique experience it was to work without a conductor, whereby all the musicians took direction from each other. do you now prefer working with or without a conductor?

Having performed with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra on an extensive tour after the recording, and after all those interviews, I came to realise why I really like working with them so much. It’s to do with the dedication of each individual – a dedication without ego and a focus on the music rather than one’s own goals – which is not commonplace. I’d say that when I have the opportunity to work with artists who are only there to serve the music, it’s as much of a pleasure as working with those conductors who are so passionate about what they’re doing, regardless of their name or their reputation. Putting that aside, there is a completely different dimension to working with or without a conductor. In fact, on this tour we played Mendelssohn’s First piano Concerto as well as Rachmaninov’s2nd Piano Concerto, which we’re playing in China and in Sydney. It felt so close and intimate with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra – so few words needed to be spoken. You certainly lose some freedom when you work with a conductor, but sometimes you have to question if those freedoms are that important. Are you doing it for a reason, or just because you’re accustomed to playing it a certain way? I think that sometimes the absolute magnetism of a group of musicians who are paying such close attention to what you’re doing is unparalleled, whereas as at other times, a conductor can inspire the orchestra in ways that I wouldn’t be able to.

What’s it like working with Krzysztof Urbański?

I absolutely adore Krzysztof. He’s one of the conductors I most enjoy working with because he is incredibly focused and dedicated. It goes without saying that he is a great musician and a great technician, but he is also a kind person both on and off stage. He is passionate about the music without being insane and it’s a pleasure to talk to him about anything you can think of. That makes a big difference to me, because I like well-rounded human beings. Krzysztof is not just a great conductor, but also a lovely person I like spending time with.

Do you speak Polish or English together?

We speak Polish. In Amsterdam, we were asked if that played a role in our friendship. I don’t think our relationship would be materially different if I didn’t speak Polish. We can just as easily communicate in English and I don’t think our shared language has changed the dimension of our friendship or music-making. I struggle to believe that blood or DNA somehow influences the way you play music. I find that my favourite Chopin interpreters aren’t necessarily Polish. Of course, there’s Krystian Zimerman who is Polish and whom I absolutely adore, but there’s also Martha Argerich, Maria João Pires or Maurizio Pollini – people who have very little or nothing at all to do with Poland, yet they still play Chopin in an extraordinary way. Cultural identity is important and shapes who you are, but it’s not necessarily fundamental for playing music in a certain way.

How do you keep it fresh, when you’ve played a piece so many times?

It’s very easy. I’m always inspired. In the case of a concerto, I’m inspired by the orchestra and the conductor’s ideas and I adopt them. If it’s a solo recital, I’m always shaping and changing. I simply work a little bit on a piece to become re-inspired and I rediscover the root of my inspiration. Another reason I never get bored is that my interpretation is constantly changing. I like exploring new possibilities. Of course, one has a certain backbone or a common theme and that’s part of your identity. You can’t change entirely the way you interpret a piece but there are always new ideas and thoughts and I’m very open to them.

You are now touring with the Australian Youth Orchestra. How important is music education for young people?

Incredibly important. It’s unparalleled. Even if it doesn’t necessarily lead to a career in music, it not only teaches you many life skills, but also an appreciation for higher art. In a society where it’s so easy to be overwhelmed by all this media and so-called 'knowledge’, it’s invaluable to have something old and traditional which requires time to understand. Classical music is not something that can just be picked up and understood in one day. That’s a barrier to entry for many people, however once you have succeeded at your own appreciation and understanding of music, I think it’s very rewarding. If we’re talking about musical education on a professional level and what the Australian Youth Orchestra is doing, I think it’s incredibly important for young musicians to be exposed to every facet of the experience. First of all, there’s the orchestral experience, which allows them to discover things that they could never learn with a music teacher in a studio. Then there’s the touring aspect, which I have to admit is rather relaxed by my standards and what I’ve experienced with major orchestras around the world. I mean, having a day off like today is a luxury and a huge expense on a typical orchestral tour. Nevertheless, the musicians get a taste of what it is like to tour with an orchestra and, for some of them, I see that it is already quite challenging. It gives them an opportunity to find out for themselves whether they can handle this type of schedule, before they decide to pursue a life of constant auditions, expanding repertoires and a career on the road. The experience of being together and performing on tour is something that cannot be explained by any other means. I’ve made it sound like it’s incredibly challenging, but for many it’s what they love to do and they find that this is what they live for and what inspires them. Look at me! I love travelling, so it’s a great combination with my career as a concert pianist.

What motivated you and Krzysztof to join the Australian Youth Orchestra on this tour?

It has a great reputation and it speaks for the incredible work they’ve done over the years for young musicians. Krzysztof and I have worked with many orchestras of the highest calibre. For example, the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival has a similar youth orchestra and we had a great experience with them. We don’t mind rehearsing. In fact, we like rehearsing. We don’t mind working on the things we enjoy. The atmosphere can be, at times, very relaxed and enjoyable, as is the case with the Australian Youth Orchestra. I’m always happy to see them again.

Is a culturally diverse youth orchestra perhaps the panacea for the ills in the world?

I wouldn’t actually specify a youth orchestra in this case. I’d say music. Somehow music survives. No matter the extent of human suffering, beautiful music has always been performed and written. That should serve as an inspiration for us and show how resilient we are as people. As a musician, I don’t ever want to make political statements because I want music to unify. When you are in a concert hall, there’s something unifying about creating great art that we all love and enjoy. Politicising that would just be taking advantage of Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin. One could say that they all had some sort of political agenda, but in the end shouldn’t we serve the greater good, without polarising an already increasingly divided world? I find that division frightening, but I see audiences and musicians, who don’t necessarily share the same political views, get along very well in the concert hall. Let’s keep it that way – as a sanctuary. |

What is your favourite dish that you like to come home to?

I have to be honest and say that I don’t cook. And I’m not a foodie, like many other people. That said, whenever I visit my grandparents in Poland, there’s a particular place I like to go and have a particular dish, which is a schnitzel with particular breading, potatoes and a pickled cucumber salad that is unique to Poznan. So yes, every time I visit them, we go there for a beer and schnitzel and it’s something I always look forward to.

Jan Lisiecki’s latest recording will be released by Deutsche Grammophon on 13 September.