Kliknij tutaj, aby przeczytać wywiad w wersji polskiej.

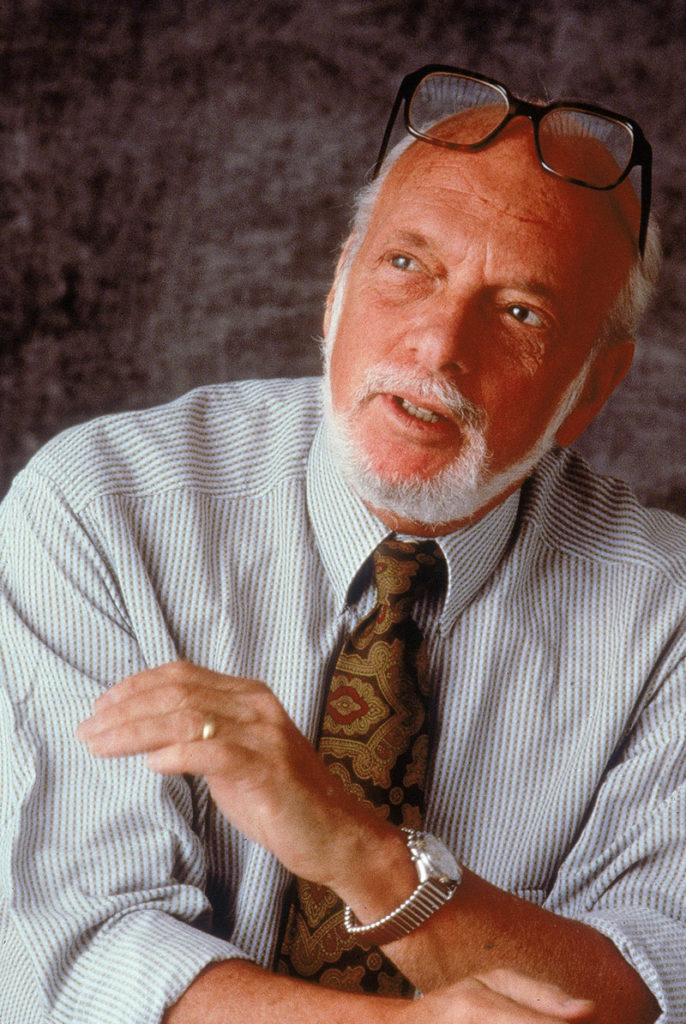

Harold Prince has just turned 90 and is celebrating the 70th year of a career that has seen him change the shape of musical theatre as we know it. Prince challenged the convention of the musical as a light entertainment and transformed it into a serious art form. The legendary producer and director is the genius behind 41 shows including the landmarks ‘West Side Story’, ‘Cabaret’, ‘Fiddler on the Roof’ and 'Sweeney Todd’. He has won a record 21 Tony Awards and his production of ‘The Phantom of the Opera’ recently celebrated its 31st consecutive year in London, and its 30th on Broadway. Meanwhile, his original production of 'Evita’ is celebrating its 40th anniversary. We talk to Prince during preparations for its September premiere at the Sydney Opera House.

Text: Jansson J. Antmann with a contribution by Clarke Dunham

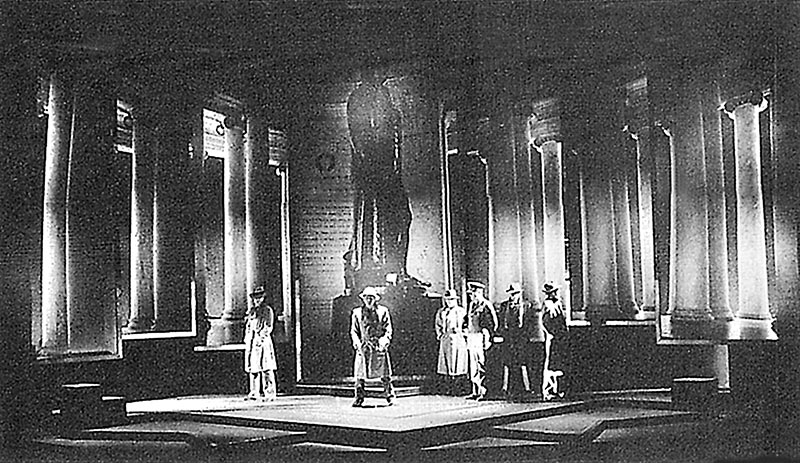

At the age of 8, Harold Prince experienced a seminal moment in his life when he saw Orson Welles perform in ‘Julius Caesar’. I am eager to learn what he remembers of that Saturday matinee, so many years ago.

“It was my first experience with dynamic theatre – with minimalism and with an abundance of brilliant ideas and great performances. In other words, total theatre.”

Prince had early ambitions of being a playwright, writing adaptations of plays for a radio station he ran at university. One of his scripts arrived at ABC-TV where the Broadway producer and director, George Abbott, was setting up an experimental television unit. Prince was offered an interview. I ask when he realised he wanted to be a director.

“At the age of 8, yes after seeing ‘Julius Caesar’, I knew what I wanted to do. Really, I wanted to be a playwright and then a director. I became a producer because George Abbott, who gave me my first job, was the most esteemed of directors and hardly needed me to direct for him. So, my partner and I became his producers.”

Prince’s theatrical career came to an abrupt halt with the outbreak of the Korean War. He was drafted and sent to Germany. Abbott promised him that his job would be waiting for him when he returned. Stationed in Stuttgart, Prince spent many an evening at a sleazy nightclub called Maxim’s, located in the ruins of a church destroyed during the Second World War. It would be the inspiration for the location of Prince’s ground-breaking production of ‘Cabaret’ several years later. Prince returned home in 1952 and went back to work for Abbott. Two years later he co-produced his first musical, ‘The Pajama Game’, which won the Tony Award for Best Musical.

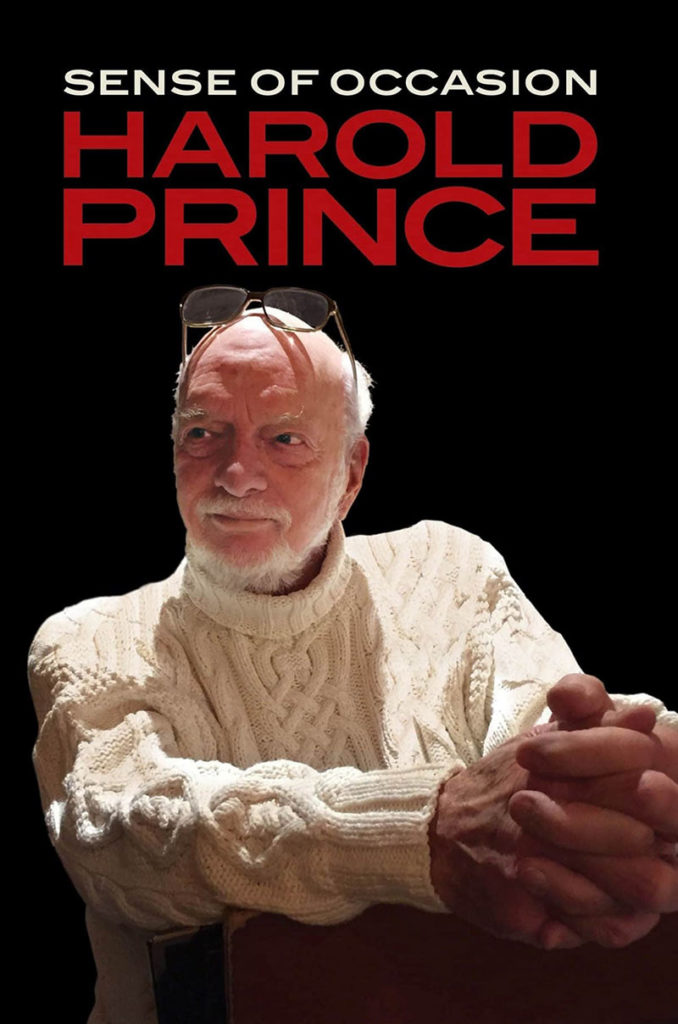

To celebrate his 90th birthday and 70 years in the industry, Prince recently released his memoirs, ‘Sense of Occasion’, which reads like a ‘Who’s who’ of the theatre industry. It should. Prince has worked with some of the most talented composers of the 20th Century, often on their earliest works. He recalls working with Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick after having seen their shortlived 1958 musical, ‘The Body Beautiful’. A year later, Prince invited them to work on ‘Fiorello’, a musical about the former mayor of New York City, which he was producing. Co-written and directed by Prince’s employer and mentor, George Abbott, it won both the Tony Award for Best Musical and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

In 1962 Sheldon and Harnick approached Prince with a work they had initially titled ‘Tevye and His Daughters’ and co-written with the playwright Joseph Stein. Prince insisted it should be directed by Jerome Robbins, who was unavailable at the time. Instead, he produced their musical ‘She Loves Me’ which, as Prince puts it, was his “first solo directing-from-scratch assignment”. The reviews were good, but they didn’t even mention Prince. Two years later, with Robbins directing, Prince finally produced the musical about Tevye, now renamed “Fiddler on the Roof” after the Chagall painting. It earned him the Tony Award for Best Producer, as well as winning the Tony for Best Musical. Prince paints an entertaining picture of how the show’s opening number, ‘Tradition’ came about.

“… there were meetings with Robbins, Stein, Bock, Harnick, and me. Quite a few long nights, all ending with Robbins asking, “But what is the show about?” The answer from the show’s authors, invariably, was “Well it’s about this milkman marrying off his five daughters …” Robbins would persist. “No what is it about?” Next day the authors gave a different answer: “Well it’s about the tough life of a Jew in Christian Russia.” Robbins: “But what’s it really about?” Finally, one late evening, Sheldon exploded: “Forgodsakes, it’s about tradition!” Robbins said, “That’s what it’s about. Write that song!”

Prince’s insistence they wait for Robbins paid off and was a natural choice. They’d both been mentored by Abbott and Robbins had already successfully directed and choreographed 'West Side Story’, which Prince had produced. During its development, Prince remembers a presentation of the new score by the show’s creators, composer Leonard Bernstein and lyricist Stephen Sondheim.

“Bernstein was very proprietary about that score: no one was supposed to have heard it, though I knew every note via Steve. […] Sondheim and Bernstein played the score, and soon I was singing along with them. Bernstein would look up and say, “My God, he’s so musical! A musical producer!”

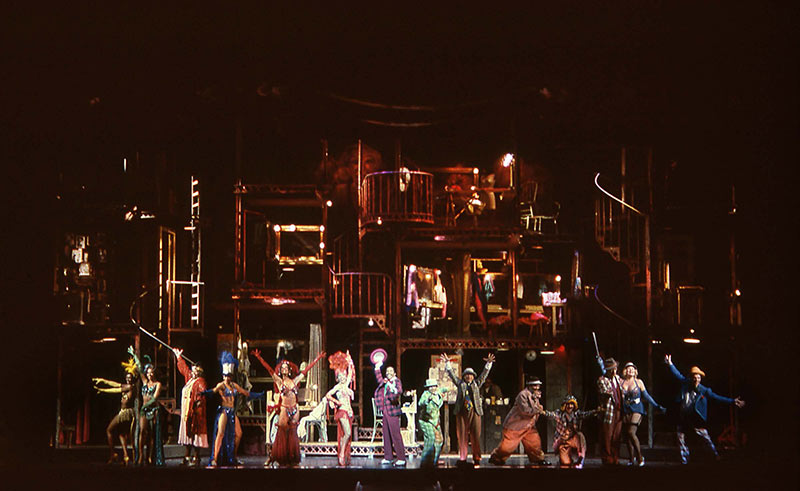

And that’s precisely what Prince was, although he would soon add the title ‘director’ to his resume and create some of the most iconic and successful musicals ever staged, including ‘Cabaret’ and ‘Chicago’ by John Kander and Fred Ebb. Prince had known both separately for some time and finally brought them together to work on ‘Flora, the Red Menace’ in 1965. It was the last show that Prince produced, but didn’t direct. It flopped, however not before it provided a young actress named Liza Minnelli with her Broadway debut and her first Tony Award for Best Actress in a musical. Prince and the show’s creators had no time to dwell on the show’s failure. In fact, as he recalls, they were already looking ahead to their next project.

“Fred Ebb remembered that the day before we opened in New York with ‘Flora’, I invited him and John Kander to my office for a meeting at 10:00a.m. the next day. [George] Abbott advised early in my career that I start work on a new project immediately after the opening of the previous one. If you have a hit, you may resent rising so early after the opening-night party. But if you have a flop, what a welcome morning it will be. So I met with Kander and Ebb the morning after the ‘Flora’ opening and presented them with Christopher Isherwood’s ‘Goodbye to Berlin’. And ‘Cabaret’ was born. ‘Flora, the Red Menace’ closed after eighty-

-seven performances, and ‘Cabaret’ opened the following year.”

Prince directed ‘Cabaret’ and it earned him his first Tony Award as Best Director of a Musical, as well as the Tony for Best Musical in 1966. He had given musical theatre one its most enduring masterpieces.

“The success of ‘Cabaret’ at the box office made the difference. I was offered plays to direct for other people.”

Arguably some of the most notable successes of Harold Prince’s career have been his collaborations with Stephen Sondheim and Andrew Lloyd Webber. Prince had already produced Stephen Sondheim’s first Broadway musical as a composer, ‘A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum’ in 1962. It had won the Tony Award for Best Musical. From 1970 until 1979, Prince produced and directed a string of musicals by Sondheim, including ‘Sweeney Todd’, ‘A Little Night Music’, ‘Company’, ‘Pacific Overtures’ and ‘Follies’. This collaboration earned Prince a further 5 Tony Awards and 4 Drama Desk Awards. Prince also directed ‘Evita’ in 1978 and ‘The Phantom of the Opera’ in 1986. Both were composed by Andrew Lloyd Webber and earned Prince two more Tony Awards as best director. The latter is now regarded as the most successful entertainment enterprise of all time. Not surprisingly, Prince is often asked about the difference between working with both composers.

“Well, for one, what’s the difference between their contributions? Steve is the preeminent composer/lyricist of his age. Andrew is a brilliant composer in partnership with a variety of lyricists, and often it works marvellously. But a better answer would address their similarities, and that’s easy: both are theatre men. Both have instincts for what interests audiences. Both have a healthy respect for the empty black box and imagination. Both are thorough professionals. They are both artists.”

Instinct plays a key role in Prince’s work too. He has often said that once he knows what a show will look like, everything else falls into place. I ask him how he knows when the look is right.

“I’m afraid that’s an impossible question to answer. It’s instinctive more than anything else and after all, this is what I’ve done with my career and I generally trust my instincts.”

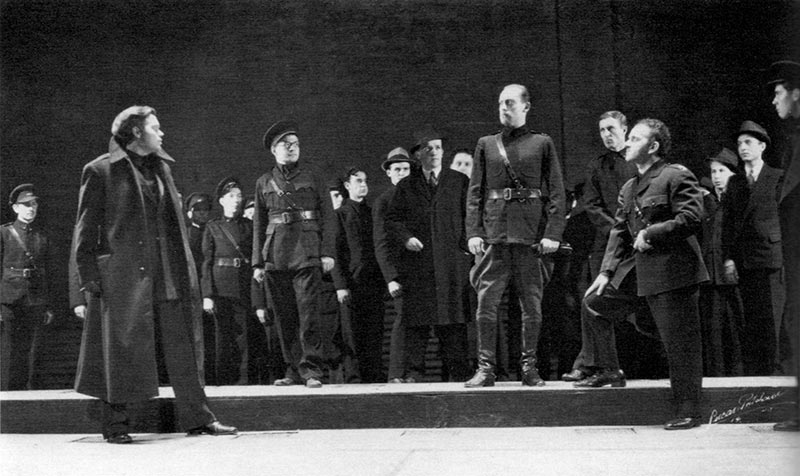

This trust has served Prince well, as has the love he shares with Sondheim and Lloyd Webber for that “empty black box”. This can, in part, be attributed to his love of Russian theatre, in particular Vsevolod Meyerhold, and Prince’s 1966 visit to Moscow when he attended a performance at Yuri Lyubimov’s Taganka Theatre. Meyerhold removed superfluous decoration in favour of constructivist scenery comprising ramps, catwalks and multiple levels. This was coupled with an emphasis on the proscenium as a bridge between the audience and the actors, who adopted a movement-centric approach to theatrical expression dubbed ‘biomechanics’. Elements of Meyerhold’s theatre are undeniably evident in Prince’s productions such as ‘Evita’ and ‘The Phantom of the Opera’. Both are deceptively minimalist in spite of their reputations as spectacles. Nevertheless, thanks to its use of a black box, projection and visible up-lighting in the stage floor, ‘Evita’ is often dubbed ‘Brechtian’, even by Lloyd Webber. I broach the subject with Prince and he is quick to rectify the misnomer.

“I am far more influenced by Meyerhold – the production of ‘Ten Days that shook the World’ was Lyubimov’s, a disciple of his. Brecht was obsessed with alienation and that’s colder. Meyerhold invited unlimited emotional responses from his audience – I prefer that.”

Highlights of Lyubmov’s production ‘Ten Days that shook the World’ can be seen in this 1974 video shot in Moscow:

Taganka Theatre – Ten Days that Shook the World from Dimitri Devyatkin on Vimeo.

Harold Prince reaffirmed his love of dramatic art in Russia when he returned to Moscow in 2016 and worked with the Russian cast of ‘The Phantom of the Opera’. During a press conference he not only praised the production, but also the way the audience reacted exactly where necessary. For a director so influenced by Russian theatre it must have been extremely satisfying to experience such appreciation of his production in its record-breaking thirtieth anniversary year.

Click here to read our previous interview with the Russian Phantom, Dmitry Ermak.

Prince has now returned to the helm of his original 1978 production of ‘Evita’ as it celebrates its 40th anniversary. Andrew Lloyd Webber has stated, “I am absolutely thrilled that my wish that Hal Prince’s wonderful production of ‘Evita’ should be seen again is to be fulfilled.” In recreating the show, Prince has incorporated a new orchestration as well as the Oscar-winning song, ‘You Must Love Me’, both of which stemmed from the 1996 movie starring Madonna. Prince is no stranger to restaging established shows. He changed the last scene of ‘Cabaret’ twice during its original Broadway run. I query the impact of the changes to ‘Evita’.

“The show just benefits from the new orchestration and the addition of ‘You Must Love Me’. However, the pacing remains the same and I believe our production is essentially a replicate of the original. I’ve always felt that was some of the best work any of us did. Larry Fuller’s choreography is brilliant and the design was everything I could have hoped for. What makes it additionally exciting to anticipate is the presence of Tina Arena and a first-rate cast.”

Performing alongside Tina Arena, in the role of Juan Peron, is one of the world’s most acclaimed baritones, Paulo Szot. The son of Polish émigrés, Szot was born in São Paulo. He returned to Poland to study at Jagiellonian University in Cracow and made his professional singing debut in 1990 with the Polish National Song and Dance Ensemble „Śląsk” in memory of Stanisław Hadyna.

‘Evita’ will be presented as part of Opera Australia’s 2018 season. It was originally labelled an opera upon its release as an album in 1976. However, it has taken 40 years for Eva Peron to find herself in the operatic repertoire alongside the likes of Carmen, Lucia di Lammermoor and Violetta. I ask Prince how significant the upcoming season at the Sydney Opera House is for him.

“Enormously significant. After all, the Sydney Opera House is one of the most important theaters on this globe. I have visited Sydney often, I have attended performances there and I always wondered whether the opportunity would arise to work there. I felt the same way about the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires, where I ultimately directed my production of ‘Madame Butterfly’, and with the Staatsoper in Vienna, where I directed a new production of ‘Turandot’. There are a number of other estimable houses that have offered my work and now: Sydney! I could not be more thrilled.”

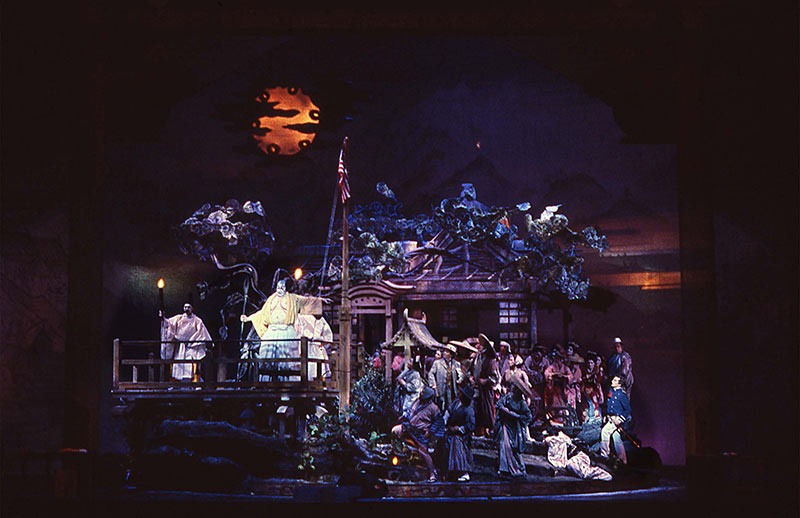

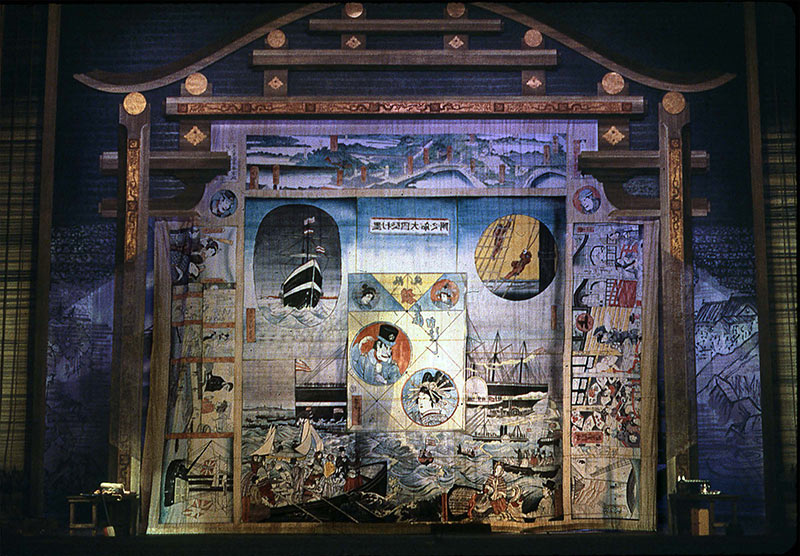

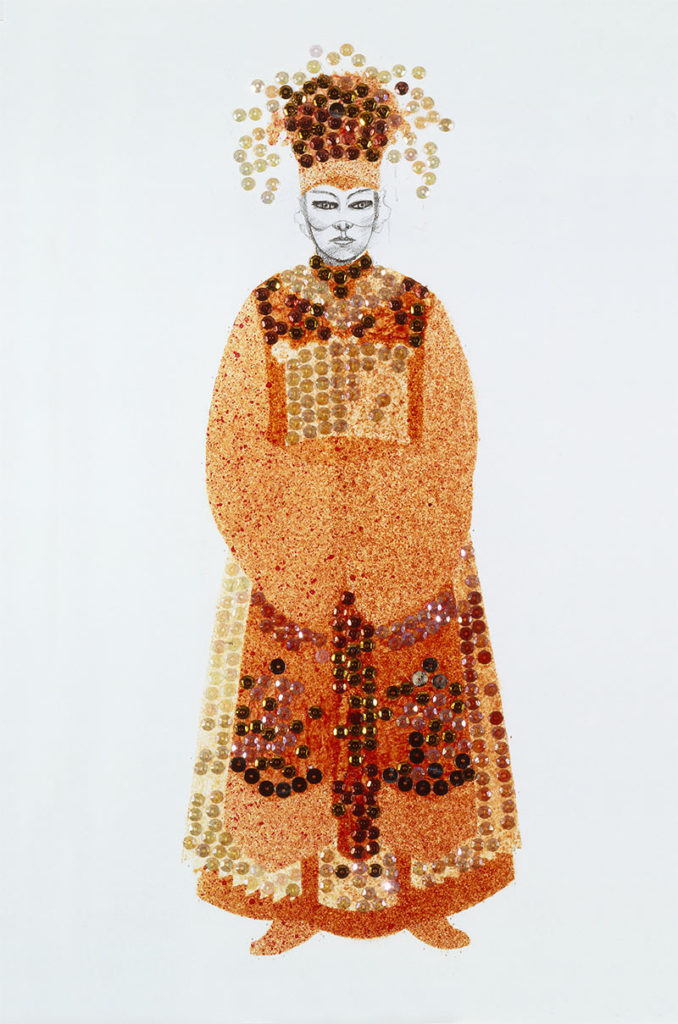

Harold Prince’s production of ‘Madame Butterfly’ was designed by Clarke Dunham and based on Japanese „Ukio-Oi” woodcuts depicting the Western Worlds’ „opening” of Japan. Prince’s 1983 production of ‘Turandot’, meanwhile, drew on traditional Chinese opera in its use of masks to achieve a sense of menace throughout. The production was designed by Tazeena Firth and Timothy O’Brien, who had also worked with Prince on ‘Evita’ in 1978. ‘Turandot’ featured legendary performances by Eva Marton and Jose Carreras under the baton of maestro Lorin Maazel. Prince made brilliant use of both the principal cast and chorus to create a sense of repressed hysteria that threatened to erupt at any moment and engulf the audience. Three years later a similar atmosphere permeated his production of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s ‘The Phantom of the Opera’.

31 years on and the Phantom continues to haunt audiences around the world. However, the Phantom is not alone. Recently Julie Andrews faithfully recreated the original production of ‘My Fair Lady’ at the Sydney Opera House to celebrate that show’s 60th Anniversary. A similar approach was adopted with the recreation of the 1964 production of ‘Hello Dolly’ on Broadway starring Bette Midler and now Bernadette Peters. And Harold Prince’s original production of ‘Evita’ is marking its 40th Anniversary this year with a world tour. Strange bedfellows? Not really. ‘My Fair Lady’ and ‘Hello Dolly’ may be lighter fair than Prince’s musicals, but they’re still works of substance adapted from George Bernard Shaw’s ‘Pygmalion’ and Thornton Wilder’s ‘Matchmaker’ respectively. In this age of 'disruption’ and 'trending’ I ask if our hunger for these classics may simply be a question of nostalgia.

“I think it’s very important in the development of an art form to revisit highlights in its history. As a young wannabe director, I believe I’ve credited everything from, yes, the ‘Julius Caesar’ when I was 8 years old to ‘South Pacific’ when I was 21 and onward. Watershed productions encourage us to aspire to watershed productions.”

Having just celebrated his 90th birthday, Harold Prince isn’t resting on his laurels just yet. In addition to the current world tour of ‘Evita’, he is also working on two new musicals. One is about autistic children learning how to realise their potential. Titled ‘How to dance in Ohio’ it is inspired by a documentary. I am reminded of Prince’s earlier account of how he found a visual metaphor for the psychological underpinning of ‘The Phantom of the Opera’. He had been watching a BBC documentary called ‘The Skin Horse’, in which handicapped people spoke about their sexuality. The second new work will look at the timely subject of gender roles. In the 70th year of his career, Prince seems to have no shortage of ideas for what to do next. However, he says the future lies in the hands of creative producers to get new shows up and running. When I ask Prince what makes a creative producer, his answer couldn’t be clearer.

“TASTE – and that is something you have to be born with and build on. Of course experiencing taste in everything – films, furniture, and décor – is important, but you have to have the acuity from the first and build. Today with escalating costs, as I pointed out in ‘Sense of Occasion’, the issue of funding productions has encroached on taste. After all, a billionaire isn’t necessarily an artist.” |

Sense of Occasion – Harold Prince

358 pages, more than 25 illustrations

Publisher: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books

ISBN: 9781495013027

www.halleonardbooks.com

Harold Prince’s memoirs 'Sense of Occasion’ are available now at:

https://www.halleonardbooks.com/product/viewproduct.action

Harold Prince worked with the set designer Boris Aronson on many ground-breaking productions. In the early days of his career, set designer Clarke Dunham worked as a scenic painter for Aronson, before going on to collaborate with Harold Prince for many years. As part of our celebration of Prince’s work, Dunham kindly agreed to share his memories of their collaboration with us.

Thoughts on a very long collaboration with Hal Prince

In early 1980, when I reminded my then Business Manager that I had just won the Chicago Jefferson Award, Chicago’s version of the Tony Awards, for my production of “Twentieth Century” and that it clearly made sense for him to tell Hal Prince about that — he was just preparing his musical version of that play, “On the Twentieth Century”, for Broadway. His reply to me was “Why would Hal Prince want to talk to you?” Those were the last words he ever spoke to me because I fired him on the spot. But it cost me a huge opportunity, not to mention precious time. My next Managers took the other, better approach, and a note from Hal soon came back in the affirmative. Hal looked through my portfolio, and at the end of the meeting said simply, “The first design opening I have is for a production of ‘Madama Butterfly’ at the Chicago Lyric Opera in 1982. Would you be interested?” The question needed no reply, and we had worked together for months when I presented a working model of Butterfly’s house straddling a huge obloid turntable that would allow the action of the piece to play out anywhere and everywhere on its terrain, thereby releasing the Opera from the traditional strictures of “Butterfly’s House”. Hal’s enthusiastic acceptance of that concept and his addition of Kabuki Theater practices to the concept left me with a feeling of having finally arrived with a collaborator who understood and would continue to take chances with my ideas. And, ultimately, for us to take chances together.

In parallel with our production of “Madama Butterfly”, but with a much later starting date, came a phone call from Artie Masella, Hal’s Associate Director, that Hal needed to see me “right away” — that night. There followed a quick trip into New York City and a meeting at Hal’s home ending in my favorite quotable Hal Prince quote — “Kid, you want the show? You got it!” The “it” was “Candide”. A very long three months later “Candide” was in the scene shop, and a month after that, in early October of 1982 the New York City Opera production of “Candide” opened at the New York State Theater. Three weeks later, Hal and I were off to Chicago for the opening of “Madama Butterfly”, whose pre-production moments had occurred months before. There couldn’t have been two more different projects than that pair of productions.

That may be, but it cemented a relationship that had already grown to include several more productions soon to come, including a new play then entitled “End of the World (with symposium to follow)”. More importantly, it gave us a chance to take a wholly abstract approach to a production, one that relied entirely on Scenic Projection as a way of producing a fast-moving cinematic solution that could keep the mulit-scene play in constant motion. As this was still the early days of onstage projection, it involved 42 high quality computer-controlled slide projectors focused on the seven screens surrounding the acting areas (nowadays there would only be seven projectors). Hal had told me that he was going to use another designer so as not to overload me, but later called to say that he knew I had more shows of his than I could handle, but he still needed me to add this one as well, and it indeed produced my first Tony Nomination. A Tony nomination ironically for a few platforms, seven screens and some furniture? The power of scene projection when used creatively!

There followed in 1985 a major Broadway Musical, “Grind”, not surprisingly about a Chicago Burlesque House, the 1996 Broadway production of (what else?), “Candide”, many repeat productions of both “Madama Butterfly and “Candide” through 2010, when both productions finally were retired after an amazing thirty-four year run. Then, of course, came the 2017 “new and very different” production of “Candide”, deeply influenced by this country’s unexpected slide into Trumpism, giving us all (and this production) a justifiably new and much more austere feeling.

Following 1987, my career took an unexpected turn with my creation of “The Station at Citigroup Center” a huge Model Railroad Exhibit that ran every Christmas Holiday Season for a full 25 years until 2008 and which my company, Dunham Studios, constructed and maintained for that entire time period. This of course allowed me to do only Hal Prince productions when called upon. What better way to end a very satisfactory career? |

Clarke Dunham

Pottersville, New York

14 April 2018

[…] In the Best of Taste […]