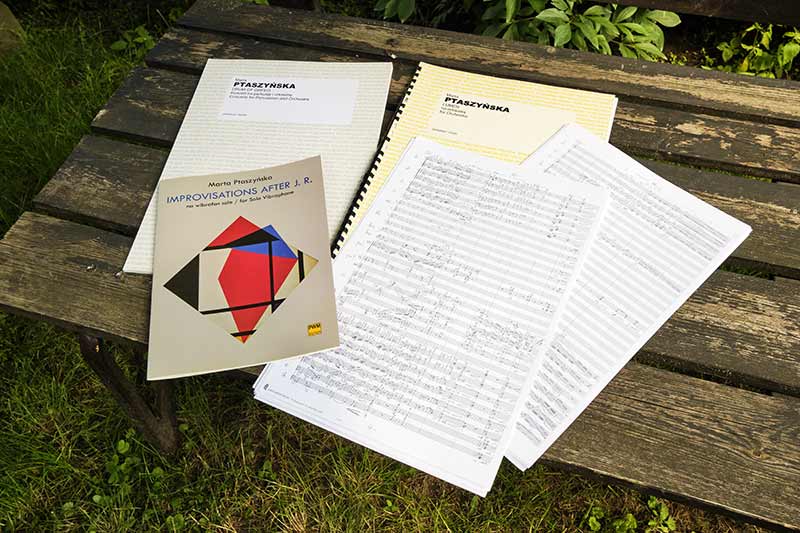

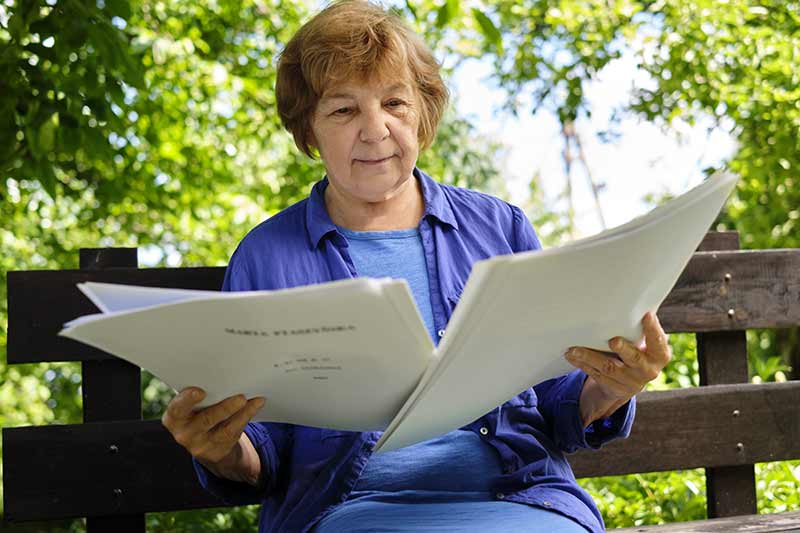

Outstanding composer and percussionist Marta Ptaszyńska has spent almost half a century at universities across America teaching composition. She has been with the University of Chicago for the last twenty years. Writing is her passion, especially when immersed in the colours of her garden surrounding the home her father designed in the Warsaw suburb of Włochy.

Text: Dorota Szwarcman

Photos: Michał Zagórny

Here we are in your lifelong home in Włochy. You were even born here, weren’t you?

Yes, but not in this house. It wasn’t built until right after the war.

And your first memories?

They’re not in Warsaw. In 1946 we moved to Wrocław, where my father had been put in charge of the railway and rebuilding the bridges ruined during the war.

The situation was critical, because at that time a huge number of Poles from the East had to move to the Recovered Territories. I remember the crowds of people. There were so many that some had to even sit on top of carriages. The first bridge that my father unveiled was the Grunwaldzki Bridge in Wrocław. I still have photos of the span being carried along the Odra River on a barge. What an incredible feat that was! I was 3 or 4 years old then. My mother enrolled me to study ballet at the Wrocław Opera, which had luckily been saved during the war and reopened at the end of 1946. I performed there as the Snow Maiden in the opera Sadko by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and also in Bedřich Smetana’s The Bartered Bride.

Was that your artistic debut?

Yes. I enjoyed it a lot, but unfortunately it came to end all too quickly. Wrocław was in ruins, with rubble in the streets. The Germans had laid mines throughout the city before they left and there were daily accidents.

My dad was worried about our safety, so my parents pulled the plug on the ballet, which was a huge disappointment for me. That was when I started playing the piano.

Was there a piano in the house?

Yes, my father played it. He loved Chopin and Beethoven the most. He had studied violin

with Stanisław Barcewicz before the war. He also knew Grzegorz Fitelberg well. I still play on the same piano my father had, but in those days it was in Tarnowskie Góry.

My father decided not to take it to Wrocław and he only moved it when we finally settled down in Włochy. In Wrocław, my parents organized bridge tournaments attended by interesting people, many of whom had arrived from Lviv. Back then I improvised on the piano and everyone liked what I was playing. That really boosted my confidence to do even more for them. There was a bookshop where we lived in Biskupin, that sold beautiful pre-war children’s books. I bought them with the little money I had and sold them to our guests, who willingly bought them. Imagine my surprise when I woke up to find the books back in my room!

They bought them to make you happy.

Yes, and I also had enough money for more. But coming back to the piano, the director of a music school in Wrocław came along one day and said that I should start taking music lessons. So my parents hired a teacher and she gave me sheet music, which I couldn’t read at the time. She played it and I remembered it by ear so that I could play it again while pretending to read the notes. I succeeded in tricking her and got away without reading music for a long time.

When did you come back to Warsaw?

On 2 April 1950. This house was built in 1948, but it was still unfinished when we moved in. So at the beginning we all lived in the kitchen, next to the tiled coal stove, which is still here today – but it’s just a memento. The accents of the olden days are still clearly visible in this house.

My father designed the house twice. The first time was at the beginning of 1939 and there were supposed to be terraces and a Venetian window. However, when he submitted the plan for approval after the war, they said, „Comrade, you can’t have it that way!” He had to therefore redesign it like a simple box, which was all the rage in those days.

A Venetian window would have been far too bourgeois! But it’s the place you always come back to.

Yes, this is my home. I feel good here and I’ve composed most of my works in this room at this solid, antique desk from 1921.

You spend most of the year in the United States, don’t you?

It’s hard to say. When I was teaching at the University of Chicago, the academic year consisted of three semesters of 10 weeks each. So I came and went from here, 10 weeks at a time. Sometimes I was here even longer, because I took time off to perform my pieces. Once I took dean’s leave and spent the entire time here. You could say that I live here and there.

Let’s go back to the post-war years when you attended music school in Warsaw.

Yes, here in Włochy. It was here that I first learnt to read music. But compared to Wrocław I found life here boring. It didn’t have the same atmosphere. The conditions were rudimentary, the house wasn’t finished, and there were no means of practising until the piano arrived.

Then you went to the high school for music.

I took piano and theory. The then headmaster of the school, Aleksander Jarzębski, came up with the idea that when you study theory, you have to choose a second instrument. That’s what led me to take up percussion. I heard my friend playing the xylophone at a student concert and I thought how easy it was, because it was like playing the piano with only the right hand. That’s when I chose percussion. I went to Mikołaj Stasiniewicz, who taught there. He was a great figure of a man. He told me, „Marteczka, it is very difficult. You’ll end up just playing on a sandbag for six months.” I said that I didn’t need a sandbag, because I could play the xylophone or vibraphone right away. He challenged me to show him, so I picked up the mallets and I think I played some Beethoven. Half joking, he said, „That’s amazing! You don’t need to study.” However, it turned out that sandbag exercises were necessary in preparation for playing the snare drum. I finally graduated from high school, firstly in 1962 in piano and theory, and again in 1963 in percussion. There weren’t many percussionists around, so I was quickly snapped up. The Warsaw Autumn Festival had begun and there was a lot of percussion in the program, so the National Philharmonic hired me. Then there was radio with Stefan Rachoń’s orchestra, and Władysław Szpilman also engaged me to record film music. I was known for my ability to sight read music, so they kept calling me. I could barely keep up with demand, because I was still studying and had to attend classes and lectures.

In addition, you studied theory in Warsaw and percussion in Poznań.

And composition too. That’s when things took a turn for the better, because Prof. Tadeusz Paciorkiewicz was teaching the composition course for theoreticians and he decided to put on a concert of our works – not in the auditorium, but in the lecture hall. Only a handful of people turned up, but suddenly the door opened and in walked Grażyna Bacewicz. She listened with great interest and then came up to me to say, „Congratulations, you should compose.” I replied that I didn’t think I’d hit the mark, because I had so much to do and was struggling to cope, but she still encouraged me to compose.

That’s quite a recommendation!

And yet, it didn’t really make an impression on me. A curious expression came across her face and she repeated, „I really think you should compose.” As a result, I transferred from theory to composition. Paciorkiewicz was still my teacher and the classes didn’t differ from the previous ones. If Bacewicz hadn’t come to the concert, I probably wouldn’t have become a composer.

One female composer inspires another at a time when it was still a male-dominated profession. Your next lucky break was meeting Witold Lutosławski.

I was already studying composition at that time. Prof. Paciorkiewicz would ask, „Dear Marcia, what do you feel like composing now?” and I’d reply, „Maybe something for two pianos.” To which he’d respond, „Oh, very good.” In those days, the Ministry of Culture was very supportive of young composers and awarded scholarships. All you had to do was submit an application, mention what you were writing, and then bring it to the evaluation. Witold Lutosławski was the chairman of the evaluation committee and somebody suggested I apply. After completing Three Interludes, I submitted the score to the ministry. A while later, an official called me to say I’d been granted a scholarship, however Professor Lutosławski wanted to speak with me. I went to the ministry and waited in the corridor for them to invite me in. Finally Lutosławski emerged to say, “Miss Ptaszyńska? I like your interludes a lot. Would you care to join us for tea?” They lived on Zwycięzców at the time.

Back then, they lived in Saska Kępa, didn’t they?

Yes, and of course I went. It was lovely, he commented a lot on my piece, but I didn’t make a note of what he said. Now, after all this time, I can’t remember exactly what he told me. As we said goodbye, he said, „When you have a new piece, please call and visit me again.” That’s how my visits to the Lutosławskis began. Often I just went to talk and didn’t bring any music. He was also very interested in what I played. When we discussed the pieces from the Warsaw Autumn Festival, he wanted to know what I thought about them, how difficult they were, and how much time I’d put in practising. We became friends. I had a percussion class while he was writing Livre pour orchester, and he asked if he could come and touch the instruments. It was extraordinary to see Witold Lutosławski arrive at the State High School of Music. Everyone stood to attention and he simply asked, „Excuse me, where is the percussion class?” He walked in and proceeded to touch the cymbals and tubular bells I’d prepared for him.

They play an important part in Livre pour orchester.

I showed him how to play and muffle them. He seemed fascinated. Then he said, „There is nothing better for a composer than to touch the instruments in person.”

Witold Lutosławski also gave you recommendations that opened many doors for you.

That’s very true. When I went to Paris to study composition under Nadia Boulanger, he gave me a letter for Olivier Messiaen. He didn’t tell me it was a recommendation; just that I was to deliver it to the conservatorium personally. When I arrived, I was lucky to find him alone in his office. I introduced myself and told him that I had arrived from Poland with a letter for him from Witold Lutosławski. He was very happy and immediately started reading it. I wish I knew what was written in that letter, because it was so beautiful to watch him read it. First he read attentively, then gradually his face brightened and he began to smile. Finally he asked me what I was doing in Paris. At that moment I remembered a story that a Brazilian colleague of mine, José Prado, had told me. He’d also come to study under Nadia Boulanger, and when he told her he’d gone to see Messiaen, she threw him out and said, „If you’ve gone to see Messiaen, I won’t work with you.” Therefore, I didn’t tell Messiaen that I’d come to study under Nadia, and I simply told him that I was a percussionist. Then he invited me to his musical analysis classes. Of course, I didn’t tell Nadia about Messiaen either. And there’s one more funny thing I must tell you. When Messiaen asked my name, I translated it into French and told him it meant „un petit oiseau” – the little bird. He was so happy that he gave me a kiss. He then took out a photo album and began showing me his childhood photos. To this day, I am amazed at the incredible way he received me.

Was it because of your name? He loved birds.

Perhaps, but I also think that the letter from Lutosławski had something to do with it. He was also delighted when I told him that I was playing with Les Percussions de Strasbourg. A few years later, he wrote that great oratorio La Transfiguration de Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ. Its first performance in France took place at the Strasbourg Cathedral in 1971 and I took part in it. Messiaen was there and he was very pleased.

How did you come to collaborate with Les Percussions de Strasbourg?

It happened during the Warsaw Autumn Festival in 1965. We performed the world premiere of Luigi Nono’s second version of Diario polacco ’58. It was conducted by Andrzej Markowski and I was engaged to play. Les Percussions de Strasbourg had come to Poznań to rehearse and we became friends. In Paris, other percussionists found out about me and started to engage me too. The French government scholarship I’d received was very small and it was hard to survive, so I was eager to play to earn some extra money. Once Jean-Pierre Drouet, the most prominent percussionist in Paris at that time, called me and said, “Listen, I’m going to Australia for a tour. Could you replace me in a concert of the Domaine Musical? Pierre Boulez is conducting his Le Marteau sans maître.” At first I refused, because in that score you have to play maracas and tambourines, which I don’t like. Besides, Boulez had a reputation for kicking musicians out of rehearsals. I had personally witnessed it happen during a rehearsal for a radio recording. He told the singer that he wasn’t suitable. At the time I remember thinking that I never wanted to play for him. However, Drouet promised to pay me twice the amount of my scholarship and in the end I agreed. The rehearsal was the next day, so I asked him to provide me with sheet music and the instruments I didn’t have. He brought them, and I practised that night. The next day, Boulez arrvied at rehearsal and didn’t even say good morning. He stood up, looked sharply and said, „Number 2.” It was the moment I was supposed to play. I played and played, and after a few bars I could see him looking at me. I tried to pretend that I couldn’t see him and kept playing. At one point he stopped the ensemble and stared at me. I did the stupidest thing in the world and started packing up my instruments, because I was sure he was going to throw me out. There was a silence and then he said, „Mademoiselle, très bien.” He’d been following my part; saw that I was playing well and simply wanted to let me know. I played at the concert, but I didn’t see him again, because he left quickly. Overall it turned out well.

How long did you stay in Paris?

For over a year, from 1969 to June 1970, but I traveled to France again to perform with Les Percussions de Strasbourg. At that time I was still taking classes in percussion in Warsaw, as well as harmony, solfege, music literature and analysis.

Nevertheless, you quickly flew out into the big wide world once again, this time for good.

In 1971 I went to the Cleveland Institute of Music to gain my PhD with the fantastic drummers Cloyd Duff and Richard Weiner. The following year, Matthias Bamert, a composer and conductor who was then working with the Cleveland Orchestra, asked me to write a piece for orchestra, so that he could perform it for me. I was a very young composer and I’d never dreamed of have having a piece performed by such a great ensemble. I wrote Spectri sonori for orchestra, and the Cleveland Orchestra really did perform it in 1973. After that, Donald Erb, who taught composition at the Cleveland Institute of Music, invited me to lecture on my work. I got my PhD the following year in 1974.

That said, your first impressions of the United States, apart from your professional ones, were not good.

No, they weren’t. It was a huge culture shock. I was unlucky, because had I gone to New York straight away, things would have been different. There were no sidewalks in Cleveland and I had to drive for two hours each way to get home. I was at the institute all day. There was no cafeteria and I had to put up with undrinkable coffee from a dispenser. On one occasion I wanted to go out to eat, and what a mistake that was. I didn’t know then that the Cleveland Institute of Music, the Cleveland Museum, and the Severance Hall, where the Cleveland Orchestra plays, basically formed an island in the centre of the roughest part of town. Nobody ventured there; everyone drove. My host family had even given me a car, because they thought it would be too dangerous for me to get around without one.

And after Cleveland?

I moved to San Francisco and that was something else all together. Like New York or Chicago, it’s a normal city, where you can walk on the sidewalks and go shopping. That’s why most Europeans prefer to attend universities such as New York University, the University of Chicago or Berkeley near San Francisco.

You have lectured at several universities.

I have fond memories of Bennington College, Vermont. It was great there. I taught composition and – for the last time – percussion. Later, from the 1980s onwards, I stopped teaching percussion, because I was receiving so many commissions to write that I didn’t have time anymore. Wherever I was engaged from then on, I was employed as a professor of composition, or more precisely as a visiting professor. Sometimes I was also a composer-in-residence, which also involved writing. After Bennington, I went to the University of California in Santa Barbara, which I also liked very much. Then I lectured twice at Indiana University in Bloomington. They really churn out musicians there.

A highly valued place in the music world.

It’s a huge institution, with about 7 orchestras. After a while, it got tiring. I was still teaching at the College Conservatory in Cincinnati, and then at Northwestern University in Illinois. Finally I got a permanent position as professor of composition at the University of Chicago, where I spent 20 years. Today, I’m not formally associated with them anymore, but I have a PhD student there and I still work with them. On top of that I am still very much involved in composing.

A few years ago, you moved out of Chicago and settled in Florida with your husband.

It was Andrzej’s idea. I’d always thought of it as a place to go on holiday, but living there permanently seemed as strange as moving to Morocco or somewhere in the middle of the desert. A person unaccustomed to the tropical climate can only stay there from November to mid-April. As a result, most of the locals are so-called snowbirds that fly there for the winter and then return to their homes.

You are also a bit of a migratory bird, as the name would suggest.

You can say that again! I prefer to be here in Warsaw. In Florida, where most of the residents are gone for six months every year, nothing really happens. It’s like a graveyard of beautiful houses and trees. In addition to the climate, I don’t like the lack of cultural activity and the monotony of life there. There is also no public transport. In Chicago, I didn’t need a car. For 20 years, I walked to the University and back again every other day. It did my health the world of good. And when I needed to go to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, I could hop on for five stops. I went to the shops on foot and I was on the move all the time. You can’t do that in Florida.

So why did you move there?

That’s a long story. Andrzej was born in Germany in 1946. His parents were Polish and forced to work. His father had to work in an aircraft factory, while his mother was sent to a uniform factory. They met at a dance and quickly got married. After the war, they were told that they could go to communist Poland or to Venezuela. The United States only began accepting prisoners of war six months later. Andrzej’s father decided that he would not go to communist Poland, so they chose Venezuela. They were there for 12 years and Andrzej went to primary school. He knows Spanish very well. He remembers his childhood there with fondness, just like I do mine in Warsaw. And Venezuela is an equatorial country and he loved the climate. For him, Florida is like a return to the good old days. He feels great there, loves swimming and visits the pool all the time. I can hardly bear it when it’s hot in Poland. And I’m glad I have this house, this desk, this garden. Besides, at any time I can go out, hop on the bus and go – let’s say – to Grycan for ice cream. Sometimes it’s the little things that matter the most.

And it’s those things that make you feel free.

Exactly. But when the pandemic came and I was in Florida, we were all imprisoned. So I told myself that I had to work in this prison and put a lot of energy into writing. It was a productive period and the compositions included a 15-minute piece commissioned for the World Marimba Competition in Stuttgart, which was to be played in the third round. It was not only technically, but also musically difficult, with an accompaniment of three instruments – clarinet, French horn and cello. There were 90 competitors and everyone had to learn it. However, last year the contest was canceled. It was supposed to be held this September, but the organizers have decided to cancel it again, because the situation is still so uncertain. I also wrote The Gates of Light for the Cracow cello-piano duo of Jan Kalinowski and Marek Szlezer. I previously wrote the Double Concerto for them as well. I also wrote a piece about the great blues singer Bessie Smith for an anthology of music for solo vibraphone. On top of that, I wrote a flute concerto, as well as a concerto for accordion and chamber orchestra. It turns out Florida’s been quite a good place to compose music. And there I was thinking nothing good could come out of that place! |