For 25 years she’s been marching to the beat of her own drum without much care for the popularity polls, even though they’ve been consistently through the roof. Never predictaible or routine, her image and artistic expression have remained authentic without yielding to fads or popular taste. Natalia Kukulska talks to us about tenderness, independence and growth – all the things that replenish her seemingly boundless enegry.

Text: Beata Brzeska

Photos: Weronika Kosińska

I was wondering whether to bring up the topic of war and only focus on your music, but we live in such unique times it’s unavoidable. Can music still provide solace in these troubled days?

There’s no avoiding it, and everything you do professionally or privately is grounded in reality. It’s something I’m having to deal with right now as well. I have the impression that artists are somewhat trapped. We all are, but artists have to face moral challenges. Is it even appropriate to peddle joy when such terrible things are happening nearby? I still cannot believe this is happening in the 21st century. As soon as the war broke out, I wanted to address it. Anyone can express themselves about anything online, and there are those who support such artistic expression and those who think it’s an attempt at exploiting the war. I sometimes can’t believe how brutal people can be in what they write. Just before the war, I shared Chopin’s Prelude in C minor on social media and wrote, Our world is ruined, something’s gone very wrong … just like my song ’Decimy’, which my listeners tend to describe as a comforting piece. As soon as I did that, an outraged hater accused me of using the war to promote my own music. I immediately blocked that person, because I won’t tolerate such behaviour or enter into such a discussion. I welcome criticism of my work, but I will not put up with such absurd accusations. Music is my domain. Words and music are how singers comment on the world around them.

People love to moralize and judge on social media.

Precisely! Moralizing, exalting themselves and imposing their morality on everyone else, as though they know how we should express ourselves and lead our lives.

I never stoop that low. I don’t understand the need to impose one’s views on others, even if it’s for a good cause. If I disagree with something, I don’t have to announce it to the whole world. I just ignore it and do my own thing.

These days nobody leaves roses on the frontline, except for us – you sing on the album Czułe struny (Sensitive Strings). Now more than ever, we cannot help but ask about an artist’s special role, or the lack thereof.

In times of war, the most important thing is bread and safety, but everyone has their own area in which they can express themselves and help. I sing, which doesn’t mean I’m not taking more direct action, although I do not talk about it in the press. Thanks to my public image and reach, I can bring some solace through music and words. During the pandemic, our artistic environment suffered a lot. Some people were left virtually destitute for a very long time.

And when it comes to closing a window onto the world, art and music offer the possibility of escaping from our challenging and frightening reality for a while. This is not a primary need, it is not bread and water, but it is food for the soul and a kind of therapy. I have never treated what I do as missionary work, but I know what helps me in such situations – a walk, the countryside, music, films, a book. That is why I believe we should do our own thing, bring joy, provoke reflection, but also elicit a smile. That’s also a panacea.

And a very real form of salvation.

On March 21, there was a concert for Ukraine, Together with Ukraine, during which I sang Imagine with Tomek Ziętek. Money raised through ticket sales and SMS pledges (approx. PLN 8 million) was donated to help Ukraine and I believe that such initiatives, unfortunately bottom-up again, bring the best results. So let’s just do our job. I am disgusted with the internet assessments of who did less, who did more, what should and should not be done, etc. I think it was Lem who said, ”If it weren’t for the internet, I wouldn’t know how many stupid people there are.”

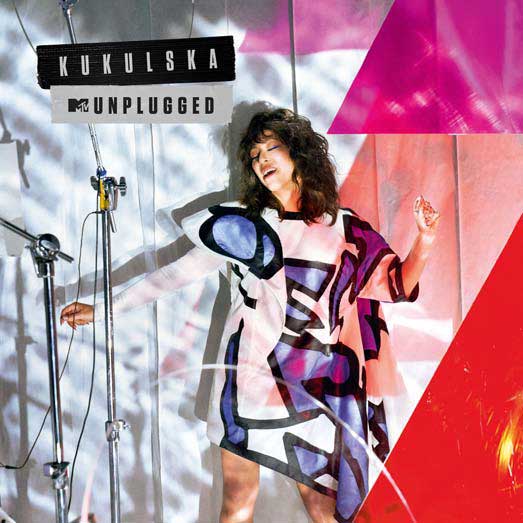

You’re riding a wave right now, what with Czułe struny going platinum, the MTV Unplugged concert, the success of your last EP with One Voice. However, that’s all been overshadowed by the pandemic, and now Ukraine. A bit like in your song Zezowate szczęście (Cross-eyed happiness).

[laughs] We are all in a similar situation. I planned many things much earlier. Czułe struny was in the making for at least ten years. I sang jazz arrangements of Chopin’s pieces at a concert with the Classic Jazz Quartet and it was a real thrill and artistically very satisfying for me. I knew that I would like to work with Chopin musically. It is known that if you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans. I also sang on the album: Halo, Earth calling: Who has power over me? I think you enjoy it. Everything is changeable and unpredictable, but you have to do your own thing … which I’ve done. [laughs] The hardest part for me was that when I finished Czułe struny, a pandemic broke out and all the concerts promoting the album were canceled. The first one took place at the Szczecin Philharmonic without an audience and it was recorded on video. When I found out when the next concert was planned, I thought: “God, will I still be alive? That’s such a long way down the track.” Fortunately, the concerts in January took place and more are planned. I am very happy because they were well received. On the other hand, Jednogłośna is proof that I have not been idle during the pandemic. I’ve been working with Archie Shevsky the entire time.

25 years have passed since your first album Światło (Light).

I avoid such milestones. The „Best of” should be more of a presentation of what I have managed to collect over the years, but in the here and now rather than old versions. We put together the album Jednogłośna (One Voice), in which there is a lot of self-reflection. I talk about the changes that have taken place in me and my approach to life. So far, an extended single has been released and I’ve started working on a whole album, but that was interrupted by the offer from MTV Unplugged. I had a month to prepare a concert with new arrangements, compositions, instrumentation – because unpluged does not mean you can just go out with a guitar. The album will be released in April and is probably the best culmination of the whole previous year and many of the musical paths I’ve taken.

It shows off your unbridled creativity with new arrangements and a surprising cover version.

I like to make my life difficult. [laughs] Archie’s new arrangements made me rediscover some of the older songs. I chose tracks across my back catalogue over the years, such as the track W biegu (On the Run) from the album Puls. I love this juxtaposition and I think that at concerts it is better to offer the audience something different to what they have on disc. It’s a value-add.

Where did the idea for the cover version come from?

MTV has certain rules: there must be a cover and there must be a guest. I have two guests: Natalia Schroeder and Igor Herbut, and the cover is Nie ma wody na pustyni (No Water in the Desert) by the band Bajm. It’s a song I listened to all the time in my childhood. And today for me it still has that special something … a kind of inside joke and lyrics that require acting. It counters the prevalent seriousness of the music industry with playfulness and pure originality. My musicians were surprised by that choice too and we had a lot of fun in the studio.

Let’s go back to your platinum album Czułe struny, which demonstrates your courage and originality like no other. You found tenderness in Chopin’s music and that became the leitmotif of the album. Until recently, we’d only heard sadness, seriousness, longing and pathos in your ouvre. Did Chopin unleash the tenderness in you, or did you find tenderness in his music?

First there was Chopin’s music. I chose the songs that resonate with me the most and themes that can be translated into the vocal line, because these are not songs written with singing in mind. Even a composition begins with quite a simple theme, all these variations subsequently emerge and my vocal „thinking” begins. That was one thing, while the other was the music that touched me the most. It was certainly not pathos. When I first sat down at the piano with Paweł Tomaszewski, I wanted to avoid the polonaises, and yet the title song is set to the Polonaise in A flat major, which contains a delicate, moving section. Everything is a matter of context and there are a lot sublime moments in this piece. Nevertheless you can find pathos in other works. I like breaking the rules; it turns me on. And tenderness somehow came about naturally. I handed over half of the album to artists I really respect.

Who were your main choices?

Kayah, Bovska, Mela Koteluk, Gaba Kulka, Grosicka – I trust them creatively and their sensitivity appeals to me. They are also artists from different worlds and that was important to me. I guess I chose singers subconsciously, because only singers can understand how difficult and demanding the melodic lines are in these pieces; what methods to adopt; which syllables sit better, and so on.

You left the subject of the text up to them?

Yes. As it turned out, their sensitivity flowed naturally. Nothing was imposed on them. For me, Olga Tokarczuk’s Nobel speech was a great inspiration. After listening to it, I wrote the text for Znieczulenie (Anesthesia) to the Prelude in C-minor in fifteen minutes. At the beginning, the girls were intimidated by the notion of writing „to Chopin” – what words to use; how to match his genius. I explained that it was not about that at all, and that they should simply write down what his music made them feel; the ideas it triggered; and how the music speaks to us today. Each of them did it in their own way. Bovska toyed with convention and imagined Chopin’s dialogue with Georg Sand. Kayah wrote a very personal lyric about the lack of self-esteem in women. Mela was inspired by Słowacki and wrote about the remnants of sensitivity in our world. For the reissue, I re-recorded Czułych strun, with Matt Dusk. We recently shot a music video for it and it’s completely different to the first one inspired by Mehoffer. Except for us tells the story of two worlds – empathetic people, sensitive to beauty in all its forms and people indifferent not only to culture and art, but also to the dangers we face all around us.

Is the reissue of Czułe struny with English lyrics and duets an indication that you weren’t fully satisfied with the first album?

A little bit. The reception to the album was very good and we wanted to give those who loved it something new, while perhaps attracting new listeners. We also wanted to make it more universal, hence the English versions of the songs. The duets with the likes of J.J. Orliński, Matt Dusk and Kayah only enrich the album.

Czułe struny is a unique release in many respects. In terms of music, it is full of original and surprising compositions with creative arrangements. The entire album brims with professionalism. Can the average listener appreciate this artistry?

I’m not interested in sophisticated criticism of what I do. This is not my motivation and I don’t demand it. Of course, I appreciate it when fellow musicians comment favourably on my work. We occupy the same world and we are able to evaluate each other’s work. The greatest joy, however, is when people are moved by what you do. It means that you have done a good job. The listener does not need to know what you’ve done to move them. All that matters is that it has that effect. I derive the greatest satisfaction from messages people write about how they listen to the album every day; the way it inspires; and how they’re moved by it. This is far more important to me than any qualified critique.

This album, like your previous ones, defies categorisation. It straddles genres, stereotypes and rules. Aren’t you concerned about the consequences of such a rebellious approach?

That may be the best compliment I’ve ever received. However, I think every artist does that, unless they’re, for example, blues or country singers, who don’t step outside the boundaries of those styles of music.

The music market, however, likes to pigeonhole things. Czułe struny was classified on Fryderyki as pop, which seems absurd.

That was such an embarrassment! I couldn’t understand it at all. We live in a cookie-cutter world and if I would stand on my head and record heavy metal, I would still be pigeonholed as a pop singer, because that’s how I started out in the 90s. On the internet, an algorithm selects songs for those who have listened to my work before, and I can’t believe what it picks. It never dawned on me that if someone liked a particular song, they’d need to create a new algorithm to keep receiving others like it. Fortunately, real people are smarter than that. What drives me toward revolution, or rather evolution, is an eagerness within me to discover new layers in myself, to open new doors and find inspiration in other musicians and anyone else I come across. I wouldn’t cal lit a desire to revolt, but definitely to evolve.

Have you had this courage and independence from the beginning of your musical career?

Probably from the beginning. It is also a matter of ambition, because of my family. I always wanted to be sure that I’d earnt my position on my own. I am constantly developing and using the gift of music I inherited wisely. I’m not imposing my independence, I just have it. To be honest, I get bored quickly. I respect other singers, but what they do doesn’t turn me on. While having one’s own style is great, I find satisfaction in the search for creativity itself.

Does your public sustain you?

Sometimes yes, sometimes no. It depends. I have found, however, that it makes no sense to work to please the majority. That’s a trap. For example, if I publish a photo with a new hairstyle online, some people will comment: How wonderful! How original! What style! while others will write: What on earth is that?! How awful! What is an artist supposed to do? Cut her hair on the one hand and grow her hair long on the other? A bit of both perhaps? This is the wrong way of going about things and I know it.Doing my own thing is risky, but in the long run I win. I am constantly working to earn the trust of my audience, convincing them that I am honest in what I do and that they will not be disappointed. However, my jaw drops when I read about myself online and my work to honour my parents’ legacy by recording cover versions of my mother’s own songs. That’s the last 25 years of my work and 12 solo albums in a nutshell. Injustice can sometimes hurt.

Performing in public and being judged by an audienceare in your genes. However, you manage to keep a wonderful distance.

It all depends on my mental condition. Sometimes it’s difficult, other times it’s not. And only distance can save us, otherwise I wouldn’t take a step. I am also saved by my sense of humour, which I inherited from my father. My mum also had one. I remember daddy’s humour, which was so abstract. He could make us laugh in the most difficult moments and relieve the situation. I tend to be deeply distressed at the way negative events affect my private life. I have three children and a wonderful family. I should be grateful for the way my life is unfolding and I have no right to worry about such nonsense. How does it relate to man’s eternal question about immortality? – my friend once asked. [laughs]

This approach can be heard in your lyrics that talk about self-awareness, a willingness to understand oneself and the world, and reflection.

That’s what Jednogłośna is like – a very self-reflective collection of experiences and traumas, which tells of the search for oneself. In your pockets you have the crumbs of your house, a dry raincoat, you arm yourself like a stage clown with jokes up your sleeve – those are the lyrics I sing in the song Nie pytaj, co będzie dalej (Don’t Ask What Comes Next). I often sing about it and the burden of the past. I was living in the past, and even if I didn’t want to, I was not allowed to forget it. I know how bad it is. You have to think about what is in the now and look ahead. And this is not just about the individual experience. Politics, history, and martyrdom are also overwhelming, limiting and prevent development.

Development is the key to your musical career. After such commercial success with the album Puls, you ended your career and left … to study.

I’m an active person. And besides, the success was a little too overwhelming. Striving for success is much more creative and liberating than achieving it.

Success and what next? It is really overwhelming. I had a dream come true, full halls of screaming teenagers, and commercial success. I lost myself. I did not have time to reflect, to distance myself, or evaluate what I was doing. I was terribly afraid of criticism, I had low self-esteem, and I was afraid of failure, because the higher one flies, the more painful the fall. Success also means being assessed, often unfairly. It can be humiliating. You have to be really tough, and that’s not how I felt. I had to change something. So I set myself new tasks and avoided stagnation.

So success isn’t your motivation then?

Definitely not. It’s fun to be successful. It’s great that there are differences of opinion that can be motivating. But I know not everyone will like my work. And there is no reason why they should. Like attracts like. A sensitivity in lyrics and music attracts the kind of person I most like to talk to over coffee. There is no artist or album that can please everyone. |